In the footsteps of the past: “The Spa” by Bojan Mrđenović6 min read

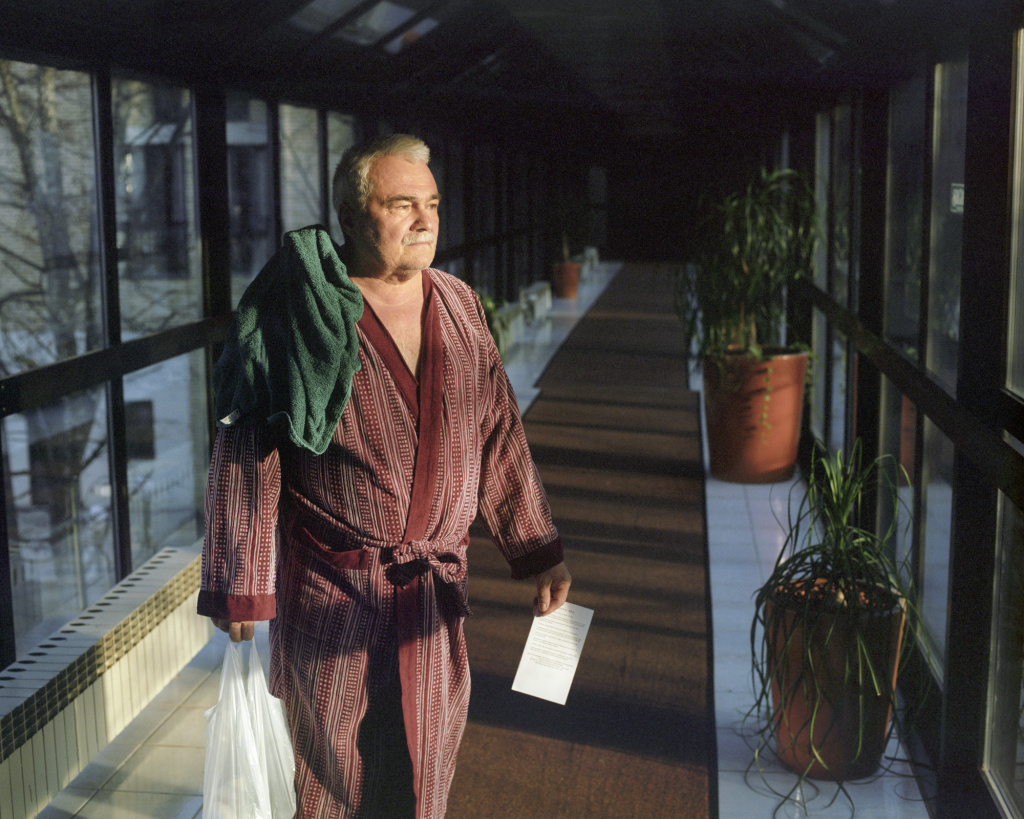

Homey, familiar, meditatively calm, and simply beautiful. Bojan Mrđenović‘s photographs from the series “The Spa” show the spa centre in Daruvar, Croatia, situated between “now” and “then.” Through visual language, the Croatian photographer turns the complex, built in the 1980s, into a political arena, and poses important, even existential, questions. What is the connection between publicly used architecture and its surroundings? And what is the role of recreational areas in a certain social value system?

Our media partner osTraum spoke with Mrđenović back in 2020 about his photo series “The Spa,” “Adriatic Postcards”, and “Welcome.”

The spa as a metaphor and a place of return

“I started this photo series in 2011, and in some ways I’m still working on it. However, recently, I’ve only been to this place a few times a year. I’m fascinated by long-term photographic observations, so I keep revisiting the objects and places in my photo series over the years.”

“The spa is in my hometown, but this project started after I had left and came back to the city as a visitor, a visitor who looks at familiar things from a new perspective. Until then I took it for granted, but then my view became more analytical. At first I was fascinated by the idea of hot water and how it is used for social purposes. I also liked the way the wellness centre looked. It is located in a park, which made me think about the interaction between the natural and built space. I also thought about the institution itself and its function. I felt that this small institution also works as a kind of metaphor. A metaphor for a certain world and a value system that I wanted to explore.”

Functional architecture in Yugoslavia – remnants of the past?

“The spa you see in the photos was built in 1980. The site was surrounded by the remains of the Romanesque period, as well as spa buildings from the 18th century, but my focus was mainly on the buildings from the 1980s. I really appreciate the architecture of Yugoslav public buildings — both for their forms and their purpose. I think this is an example of modest and functional architecture that really takes into account its surroundings and enters into a dialogue with them.”

“The moment I started walking around and taking pictures, I saw that some restoration work was being done. The rooms were partially renovated, some changes were being made to the façade, and some of the interior was being restored or removed. This stimulated my archaeological impulse, and I understood that I wanted to capture the spa as it is now through the pictures.

I am drawn to community places — the places that people share and shape. Our built environment always reflects social dynamics and contains varying levels of political implications. But I also like to think about the opposing influence that certain types of social places can have on the people who use them.”

The idea of well-being as a political question

“The spa complexes of this type have a dual function: they serve both medical and tourism and recreation purposes. The medical treatments for all patients are paid for by the state health system, while tourists have to cover the costs themselves.”

“This reflects the legacy of socialist management, as treatment is free for all those in need. I find this component very important for the identity of this place, but I wonder whether it will continue to be this way. There are more and more initiatives to bring social services onto the market. This means that they are only available to those who can afford them.

Many spa centres in Croatia, and in neighbouring Slovenia, for example, are privatised and profit-oriented. The same thing happens with hospitals. Almost all new hospitals built in Croatia in recent years are private. Throughout the pandemic crisis, however, it has become clear that people’s health must be supported by institutional infrastructure. And just as individuals, institutions must also be taken care of. So I tried to articulate the idea of well-being as a political issue using visual language.”

The resorts in Croatia in slow motion

“The photo projects “The Spa” and “Adriatic Postcards” show places that have been set up for people’s well-being. Through the development of these institutions, one can trace significant political changes over the last 30 years. In the socialist state, the institutions were developed by the public for the public, while in the capitalist state — by elites for elites.”

“I have also worked on some other projects that relate to the ideas of well-being and tourism. In my short film The Party I tried to make a sketch of the party night on one of the popular Croatian islands. In another photo project “Adriatic Highway”, I used my bike on the highway that stretches along the Adriatic coast to trace the intensive development of the tourist infrastructure.”

The “local” vs. “tourist” or the feeling of belonging

“I have lived in Croatia all my life and it is a territory that I know quite well, with all its diversity and subtleties. I like working with small themes that reflect larger dynamics. I find that the objects and themes come to me quite naturally from everyday life and my familiar surroundings. I feel like a citizen of the world and have no strong connection to national identity. But there is still a kind of belonging that comes from geography. There is a certain area where you feel at home, an area to which you are more connected than to any other area.”

“For me it is important to focus my interest on the area I have a personal connection with. I don’t think that these relationships and the feeling of belonging are predetermined. I think they develop over time and that is what makes the difference that is visible between the “local” and the “tourist.” I would also like to work on photography in other countries, but I don’t feel it is a necessity. I think that I have a lot to do at home too.”

New projects and contemporary Croatian photography

The architecture in public spaces is definitely a long-term topic for Bojan. The photographer is currently working on new projects in this area and also on another project related to industrialization and environmental issues. The sources from different photographic archives are coming into play in his work and that makes the process really interesting.

You can continue to learn more about contemporary Croatian photography on the curated website called Contemporary Croatian Photography, which Bojan shared with OsTraum: “… [it] presents the work of many authors that I admire, such as Hrvoje Slovenc, Marko Ercegović and Boris Cvjetanović. If I had to choose one person, it would be Ana Opalić. From the young generations of photographers, I would recommend Glorija Lizde.”

This article was originally published in German on 21 July 2020 by our media partner osTraum.