A journey through history and memory: Exploring identity and belonging in Lena Wolf’s “May the Universe be Your Home! A German-Russian Story”12 min read

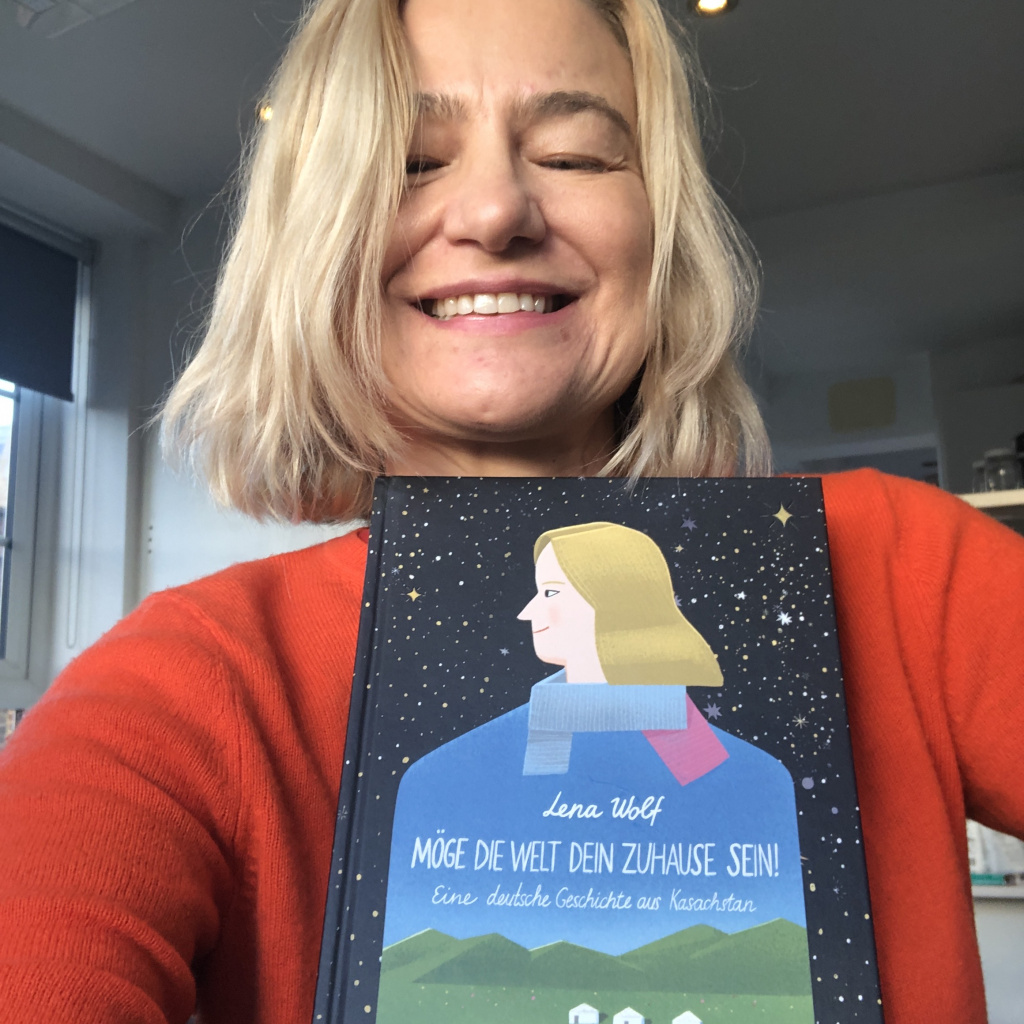

Lena Wolf, author of the graphic novel May the Universe be Your Home! A German-Russian Story, set out to share her and her family’s story of identity, belonging, and tragedy.

Now based in London, Wolf grew up in Kazakhstan with her parents and grandmother who were Germans living in the Russian Empire, and later the Soviet Union. They, along with many other ethnic groups, were deported east under Stalin.

Inspired by other graphic novels such as Persopolis, They Called Us Enemy, The Best We Could Do, and Heimat: A German Family Album, Wolf’s goal was to make this little-known history more visible. Lossi 36 sat down with Lena Wolf to discuss her story.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself, your background, and your graphic novel, May the Universe Be Your Home?

Lena Wolf: I was born in Latvia to an ethnically German family, but grew up in Kazakhstan. So I consider myself a German from Central Asia. Both my parents are Germans, but they’re Germans from the Russian Empire. My ancestors settled in the Russian Empire in the 18th century, living there for 150 years before the Second World War. It was during the war that Stalin decided that all ethnic Germans were enemies. And that’s when the persecution started.

One of the goals was to write about this history that not many people know about, and make it more visible. May the Universe be Your Home! is about a search for identity. The graphic novel begins from Lena’s perspective in London, who doesn’t quite understand who she is or where exactly her family is from. To explore those questions, she goes back in her memory to the Soviet period in Kazakhstan, where she grew up.

It was important to show this conflict of Lena as a young child, being a happy, young person growing up and being a Pioneer and believing in the communist system that takes care of her. And then being confronted with the stories of her grandmother about the harshness of what it used to be like which nobody seems to be talking about. In order to understand ourselves, as is very often the case, we have to go back and explore our past. And it’s only after Lena clarifies those questions and researches a bit more about history, that she understands where she comes from and who she is, that she makes peace with herself.

At the end, she is happy to see herself as a whole puzzle, not just little pieces that are missing, but the whole of who she is. It’s finding identity, but it’s also about dealing with the inheritance of trauma. Many of us have family histories, and some are lighter or heavier than others. So it’s about how to deal with the history that is passed on to you.

In the story, your mother suggests you write down your family history on paper. Was this what inspired you to share your story? Did you know you would create a novel at this moment?

No, to start with it was just about putting the puzzle pieces together. I wanted to understand our history because there were so many gaps and I couldn’t see the whole picture. For example, how exactly did the deportation happen? Why did we end up in Kazakhstan? Why did some people end up in Siberia? What happened to those women and children that were deported, what was their situation like? Did we do something to deserve it? I wanted to clarify all of those things. I had some of the stories from my grandma, but there were still gaps. And so when I first started, my mom said, “Start writing it down and maybe it will make sense.”

I started by researching and reading books until I had a fuller picture. Only when I understood more or less our history and after talking a lot with my parents, then I realised that my nieces, nephews, and even my friends — who know me as a German in London — still don’t know where we come from. That was the first time I had the idea to create a graphic novel.

An advantage of a graphic novel is that sometimes you don’t always need to use words to describe something. Pictures can speak louder than words. Sometimes we also used specific colours when we wanted to emphasise something. Originally, it was in black and white, like many graphic novels. But I realised that to describe the mood, I wanted people to see the colours of Kazakhstan. I wanted people to see the blue sky. While some parts have lighter images to convey happier times, the section where we have started to use dark colours is the deportation.

Graphic novels are a great medium to present difficult topics and express them sometimes without words.

How did your family react to the idea of you telling their story through a graphic novel? Were there any concerns or hesitations?

I think graphic novels were very new to them, and my relatives didn’t quite fully understand my project. They just thought: “Lena is a bit strange and we just support her in her strangeness.”

In the beginning, my mother was surprised that I wanted to write a book. My parents’ generation didn’t want to talk about the tragic history or burden anyone with it. My mum didn’t fully think anyone would want to read it. I had to explain to her that people actually want to, and what convinced her eventually was when I was invited to South Dakota to do a presentation on the book. She was completely stunned that someone in the US would want to hear our story. That was the turning point.

Are there themes in your book that resonate beyond your own family?

The topics discussed in my book are quite international in terms of how many countries and peoples have experienced persecution based on ethnic background. In this case, it was in the Soviet Union. When I was growing up, there was this idea of everyone being equal and all nationalities and ethnic backgrounds were welcome. But there were certain ethnic groups — and we never talked about it — that for some reason were not welcomed.

In my book, I wanted to tell people how it was not just the Germans from the Soviet Union who were deported. I make sure that people also understand that there were about 22 other ethnicities that weren’t seen as sufficiently Soviet.

The Soviet Union promoted equality by eliminating other identities and replacing them with a Soviet identity. As a child, I wanted to be a Pioneer because they were on TV. Speaking Russian was seen as cool while speaking Kazakh and German was not, and we did not have representation in TV, movies, or music. Most of my Kazakh friends didn’t even speak Kazakh. You will be equal by speaking Russian. If you grew up with it, you don’t see that. You only realise it as an adult.

Recently, I read about Koreans in Kazakhstan and how the younger generation no longer speaks Korean due to deportations that erased their language and religion, replacing their cultural ties with Soviet identity.

One of the beautiful things was that I grew up in this incredibly multicultural environment. In Kazakhstan, there were Tatars, Armenians, Koreans, and so on. It was this wonderful mixture of people, represented in the colourful food, interactions, different languages, and different clothing. I like that part of Kazakhstan. For me, that part was fun. But of course, when I was young, I didn’t know that we were all children of deported people.

What is the most surprising thing you learned writing this book?

One of the biggest things that I learned by researching this book is how this history that I thought only relates to my family, or this minority that I come from, affected so many other minorities in the Soviet Union, and elsewhere too. If you look at Poland, the Czech Republic, or Romania, there were deportations there as well. People identify with and know this history, but again, nobody talks about it as much.

Another thing that I didn’t know before is that, when the Soviet army marched into Poland, they took a lot of people, put them on trains, and sent them east. They sent them to Siberia or to Kazakhstan, to the Gulag. When I started working on this book, I came across Babushka’s Journey: The Dark Road to Stalin’s Wartime Camps by Marcel Krueger. It’s about his grandma who was deported from Poland on one of those trains and sent to Gulag camps in Siberia and then to Kazakhstan. When she returned to Poland, there was nothing left of her home and there was nobody left either. Eventually, she ended up in Germany and started a new life there.

What challenges did you come across in writing May The Universe Be Your Home?

While writing the book, one of the scariest things for me was when I started posting about it on Facebook. I was terrified by angry comments, especially from Russian-speaking men. I posted something about the history of Soviet Germans on Facebook and had people swearing at me. But you learn to deal with it. I became more careful about what I post, but I also blocked aggressive people.

Another challenge I encountered was, before the war, I went to the Russian consulate to get a visa to go to St. Petersburg for my friend’s wedding. They declined my visa, claiming there were no Germans who lived in Russia, and kept confusing Russia and Latvia. They asked, “Were you born in Russia?” And I answered no, because I was born in Latvia. They didn’t ask if I was born in the Soviet Union. And then, “Have you ever lived in Russia?” And I again said no, because I lived in Kazakhstan. When I explained we left the Soviet Union because we were a German minority, they showed me a list of minorities in Russia, but no Germans were on it.

I remember standing there with my heart pounding, I felt this mixture of being angry, but also so upset that I wanted to cry. Even now, they tell me that we didn’t exist. That was very surprising, overwhelming, and disappointing, all at the same time. It made me question whether I wanted to go to Russia again. But then it also made me realise this book was needed. The Russian speakers to whom I gave the book got back to me saying, “I never knew anything about it,” and “Well, we knew that there were some Germans, but that they were in Gulag, probably because they were Nazis.” Even one of the girls who helped me with the Russian translation, came back to me saying, “My God, really?”

I tried not to accuse anyone, but to tell the stories as my grandma told me or as I understood them from my research. I’m not sure if there’s even anyone to blame. All I wanted was to tell my story, so that people know and can make up their own minds.

What has the process of writing and illustrating your family’s story taught you about your heritage and personal identity?

It changed my perception of myself quite dramatically. Before I started writing this book, questions about my identity or origin were difficult to answer. Am I German? Am I Kazakh? Maybe I’m Latvian or a mixture of all. Who am I? It was a simple question, but for me, it was a 20-minute discussion that was complex, especially because I didn’t know my whole history but knew the pain. I could never answer “Where are you from?” in one sentence. I couldn’t say “I’m Russian-German” because people misunderstood it. I couldn’t say “I’m Soviet-German” because people then say, “So you believe in communism?” There was no word I could use to describe myself. In the end, I resorted to saying “Kazakh German,”and now I would say I’m a German from Kazakhstan.

After finishing this book, I’m sure about myself. I know my history. When people ask me any questions, I can answer them with ease. This gives me a lot of stability and understanding of myself and who I am.

What do you hope readers will take away from your story?

The importance of knowing who we are, remembering our family, listening to our grandparents, and passing on the story. Now I’m becoming the person who passes on the knowledge to my nieces and nephews. We are not people without roots. We have our own stories and they make us who we are, we are the stories we tell. It’s up to us if we tell only tragic stories or if we find and pass on the good parts.

The most important aspect is family, which gets passed on through stories or food, through gardens or knitting; all these things that we take for granted but we realise were little acts of beauty even in the darkest memories. Every story has beautiful parts to it.

˜ ˜ ˜ ˜ ˜

Lena Wolf’s May The Universe Be Your Home!: Growing up German in Kazakhstan is available for purchase in English, German, and Russian. Wolf is planning to write a sequel that tells the story of her grandmother Josephine, who was sent to the Labour Army and then the Gulag for 20 years, and her father, who ended up in an orphanage in Ukraine. More information can be found on her website.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.