Remembering Reality: The Challenge of Keeping Stalin’s Painful Legacy Alive12 min read

Joseph Stalin left behind a bloody legacy. Countless millions of Soviet citizens met their end as a result of his policies. For some, this meant whittling away their foreseeable future in a labour camp. Others were liquidated even more swiftly by NKVD officers. Not even those in Stalin’s inner circle found sanctuary in his proximity. Stalin died in March 1953. In 1956, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, launched a project of ‘de-Stalinisation’, in which Khruschev and his government tried to disassemble the cult of personality that had built up around Stalin. But over 65 years later, crowds still gather on the anniversary of Stalin’s death. He may be long gone, but his legacy lives on and his presence is palpable. Throughout the past decade, public sentiment towards Stalin has been in flux. Any attempt at figuring out the narrative behind this development has been difficult. With that being said, positive feelings towards Stalin have increased sharply in the past two years. according to data collated by the Yuri Levada Center. For anyone who knows about the Gulags and the NKVD, this is hard to comprehend. So exactly what has been happening? Who or what is driving this change in social attitude?

In 2018 the Yuri Levada Center asked respondents if they agreed that Stalin was a cruel, inhuman tyrant who was guilty of killing millions of innocent people. Support for this view has decreased dramatically since 2008, with more and more respondents unsure whether they agree or disagree. The agency does not mention what informs or prompts the statement which signals that certain assumptions exist in Russia regarding Stalin. In 2019, 7 out of 10 Russians felt that Stalin had played an overall positive role in Russian history. The older a respondent was, the more likely they were to attribute either admiration, respect or affection and fondness as opposed to enmity and irritation, fear, revulsion and hatred. Now we must wonder, is Stalin popular because of his brutality or in spite of it? After all, a lot of the oldest generation in Russia grew up when Stalin was in power.

First, we need to figure out what we talk about when we talk about Stalin. When a Russian citizen is asked what they think of Stalin, exactly what is evoked in their mind? 2019 saw the highest report of respect towards Stalin in the survey in at least twenty years which has climbed steadily since Putin embarked on his third term. Opinion barely budged during Medvedev’s four-year stint as President. So, do people respect the man or the method? Oliver Stone’s The Putin Interviews (2017) brings intimate conversations with Vladimir Putin to the public. Putin quips that demonizing Stalin is to attack the Soviet Union and Russia. Conflating these two things makes it difficult to deal with.

Groups behind projects like The Last Address who affix plaques bearing the names of repression victims to their last known addresses – similar to the Stolpersteine which recognise victims of the holocaust across Europe want to shine a light on both sides of the coin here. Not just the side minted by the current administration. Does this mean readdressing the balance is to attack the Soviet Union and Russia? Does this also suggest frustrated citizens like sports journalist and controversial documentary maker Yury Dud are attacking Russia by using their platform to draw attention to the horrors of Stalin’s legacy? Is it unpatriotic to take an accurate reading of the Stalinist era?. In spite of civil society efforts to educate the masses about the method, the popularity of the man rises. Just as Stalin’s ideological writings were edited to agree with his political stance as it morphed throughout his tenure, so too has the state been editing the mass transmission of his legacy.

Stalin’s link to Russian patriotism is largely founded on his leadership through WW2. The war sits on emotional territory within the Russian collective psyche. Post WW2 Europe had to come to terms with the horror the war had left behind. In Sergei Medvedev’s 2019 offering, he compares dealing with the awful memories of repression to Germany’s post-war dealing with Nazism.

Largely, Germany has moved on whereas Russia is yet to have its Nuremberg Trials to publicly condemn Stalinism. That is not to say that Nazism and Stalin are alike but both left a destructive legacy. According to Russian public opinion research centre VTSIOM, fewer than half of 18-24 year olds are aware of widespread repression under Stalin. Older generations tend to be more informed. Not only are older generations struggling to come to terms with the past, the youth are missing the bigger picture. This statistic concerning the youth of Russia is a golden opportunity for the state to force its own reading of Stalin’s history.

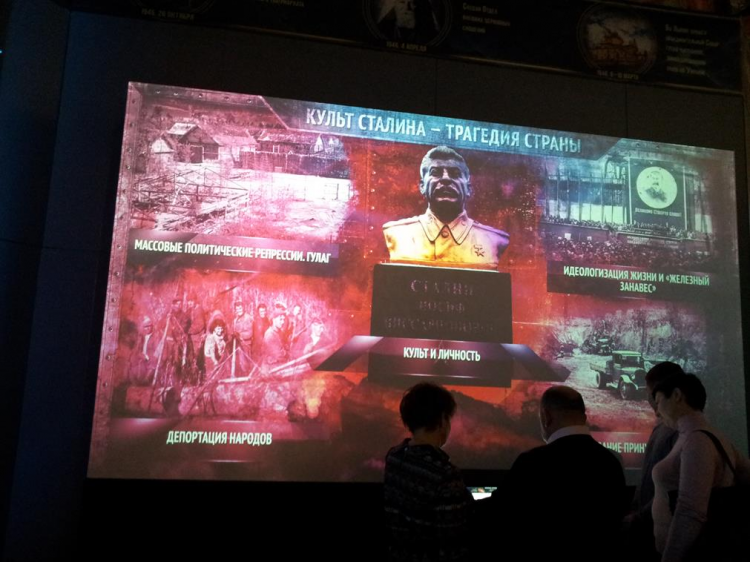

You can find glossy, ultra-modern, ‘Russia – My History’ exhibitions in most major cities in Russia. These exhibitions use multimedia displays to engage all ages in epochs of Russian history stretching back to the Rurikovich dynasty which ruled Russia before the Romanovs took their place in the early 1600s. Some of the 20th century exhibitions even spill over into the current era and touch on various aspects of the Putin saga including up-to-date installments documenting recent tribulations in Crimea as well as touch screen fact-files celebrating the successes of the Russian government.

Putin visits the Russia – My History exhibition in Volgograd. Source: en.kremlin.ru

While some tangible historical artefacts are on show such as the wrecked ship in the Volgograd park, for the most part, the exhibitions are set up like interactive galleries. Facts, figures, paintings and portraits are collaged together and stuck to the walls. A walk through the St. Petersburg park gives a good impression of what to expect from a visit.

Children and teenagers can visit the exhibitions for free, making the parks an economical and educational family excursion. Younger visitors might jump at the chance to build a virtual Soviet fighter jet whilst older generations can take a nostalgia trip through the digital mock ups of Soviet apartments throughout the past century. Either way, the contents are wide ranging and offer plenty of distractions from the less savoury facets of Stalin’s USSR. The exhibitions draw attention to the more agreeable aspects of Stalin’s reign, like his leadership and eventual victory in World War Two. Violence and repression under Stalin are mentioned but explanations and further details require more thorough reading of the electronic books littered throughout the exhibition. A game-show atmosphere adds plenty of distraction and entertainment value to Russia – My History.

Part of the 20th century exhibition in the Moscow park. Source: uborshizzza.livejournal.com

Distinguished Soviet historian Marlene Laruelle joined the ranks of those concerned with the messages these federally funded parks transmit to the public. Instead of focusing on the disastrous impact of Stalinist policy, the parks prefer to portray these policies as a restoration of national ideals that the Bolsheviks fought to drag Russia away from. Laruelle points out that the parks channel a conservative interpretation of Russia’s rich history. The Russian Orthodox Church has been profoundly involved in the creation of Russia – My History, stating that the February revolution embodied liberalism and Western perspective on the world. That is then framed as something that has led to Russia’s demise. Ivan Kurilla of the European University in St. Petersburg has also weighed in by drawing attention to the fabrication of quotes and outright inaccuraccies present in the parks.

Another attraction, Moscow’s GULAG History Museum, informs younger generations about labour camp life under Stalin. Financed by donations, the exhibition created and printed a graphic novel telling the real life stories of people impacted by repressions. Further East near Perm, a preserved Gulag has been serving as an exhibition to repressions since the 1990s. Timber logging camp Perm-36 has aimed to educate visitors about forced labour that came as part of the package of punishments at the Soviet leader’s disposal until its foreign agent branding received in 2015. With the iron barely cooled on snow laden Perm-36, conservative local government officials commandeered the organisation which now offers a reading of the camp’s history through a different lens. Perm-36 now emphasises the importance of the back-breaking logging work that went on and the camp’s place in the victory of the Second World War. Despite state interventions in directing the memorialisation of Russia’s past individual voices manage to break through. Notorious mining camps in the Kolyma region received a great deal of attention recently.

VTSIOM’s survey motivated journalist Yury Dud to shine a light on not only the hardships of living in the harsh climate of the region but also the stories of relatives of those who experienced the camps and perished. Dud, a sports journalist by profession, refers to Kolyma as a citadel of Stalin’s repressions. He put together a disquieting two-hour long documentary including interviews with descendants of the citizens living around the prisoner built Kolyma highway. Almost 20 million viewers have visited the popular youtube page in less than a year. Such popularity signals a great deal of curiosity on the subject. People are interested in the past despite the roadblocks diverting the public to a state informed reality of what happened under Stalin’s rule.

Cinema, a more traditional storytelling medium has been less successful in approaching the subject. The Russian Ministry of Culture has had a hand in preserving Stalin’s image. Armando Iannucci’s English-language satirical film Death of Stalin (2017) documents the scramble for power and scheming that went on in the immediate aftermath of Stalin’s death. While Iannucci’s film earned awards and nominations in the West, the Russian Ministry of Culture was less enthused. The film was denied a distribution license in Russia, making it essentially banned. Moscow’s Pioneer Cinema screened the film once, but was soon after visited by the police. They cancelled all subsequent screenings.

A similar story unfolded with Ridley Scott’s Child 44 (2015) in which the government under Stalin covers up a horrific crime to save face. The Ministry of Culture deemed the film “historically inaccurate”, and it was pulled from cinemas one day before release.

Likewise, the 2019 film Mr. Jones, about the British journalist who reported on the Holodomor, the mass starvation of Ukrainians under Stalin’s agricultural policies, has not been scheduled for release in Russia.

The Ministry of Education has been selective in the history books it allows in its curricula. In Yekaterinburg, history textbooks authored by famed British military historian Antony Beevor have been prohibited for their discussion of Nazism in relation to the Second World War. World War Two is something acutely important to Russian cultural memory and serves as a rallying point of patriotism stretching across all of Russia. Stalinist Repression reached its climax just before World War Two broke out and exists its shadow in cultural memory. Stalin is hugely celebrated as a hero as part of this cultural memory. Caution is being exercised by the authorities in their sanctioned portrayal of Stalin to avoid tarnishing this topic of national pride at a time where patriotism has been identified as a key ingredient to Putin’s popularity.

As well as that, Moscow State University Professor Andrei Suslov’s guidebook for teachers to explain Stalin to school pupils was banned after Essence of Time, a revisionist civil society movement who mourn the fall of the USSR, led a campaign suggesting it was bad for children’s health. 18-24-year-olds were also reported to be the most indifferent towards Stalin. Stalin is an age away from living memory for this group which gives them only his reported legacy to base opinions on.

Visual representations and their associated opponents are some of the more visceral and telling signs of changing attitudes towards Stalin. Even though 26% of citizens responded with indifference towards Stalin, that didn’t account for almost 12,000 citizens petitioning against the proposed placement of a monument of him in Novosibirsk, a city to which Stalin forced thousands of citizens to relocate. It is no wonder that the city has been in a resentful mood. This comes amidst a deluge of new monuments and visual depictions of Stalin across Russia.

Stalin bust in Novosibirsk. Source: rferl.org

Work was completed in 2017 on the Wall of Grief, a monument memorialising the victims of Stalinist repression. Putin unveiled the wall, expressing that victims should not be forgotten. These remarks bolster the undercurrent of remembrance as citizens still gather in Moscow’s Lubyanka Square overlooked by the former KGB nerve center to recite names and details of repression victims. it appears that Putin is attempting to take a balanced stance towards the issue opposing severe demonisation of Stalin. To the contrary, FSB director Alexander Bortnikov has said Stalin’s repressions were justified. Speaking to Rossiyskaya Gazeta – one of Russia’s most widely circulated newspapers – he feels that they were necessary to fight against the enemies of the RSFSR and the Union more generally. While this shows plurality of opinions, on the significance of Stalin’s legacy, only one is celebratory.

Under policies of openness, Gorbachev encouraged reinvigoration of Soviet society by way of denouncing Stalin’s legacy. As did Yeltsin. Putin’s reign has seen gradual rehabilitation of Stalin’s memory which has only shown signs of stagnating under Medvedev’s Presidency. For an outside observer, pinpointing why these sudden changes are occurring in Russia is challenging, as is separating Stalin from Stalinism. The Russian education and culture ministries make this difficult for Russian citizens themselves. Many want to remember Stalin as a hero who led Russia on a path of international successes.

A shift is happening on a grassroots level but the state’s appetite to manage the image of Stalin remains. The legacy of Stalin is pervasive. His memory transcends age groups and other demographics. You would be hard pressed to find a Russian citizen who didn’t know who he was – even if the youth are less acquainted with his capricious side.