“The essence of Georgian fine art of the postmodern period”: The legacy of Soviet Georgian mosaics11 min read

Soviet Georgian mosaics are widespread throughout the country, yet many face serious neglect since the collapse of the Soviet Union. While academic activists and civil society have done much to restore these pieces of Georgia’s artistic history, much work still needs to be done to showcase and celebrate the diversity of mosaics from the Soviet Georgian era.

Mosaics, as a form of monumental-decorative art, served several specific functions during the Soviet period. Through the synthesis of art and function, mosaics were able to promote the Soviet system and glorify Communist ideas. Placed in public spaces, Soviet mosaics were the modern-day religious fresco, teaching Soviet citizens what was expected of them and creating a “unified ethic.”

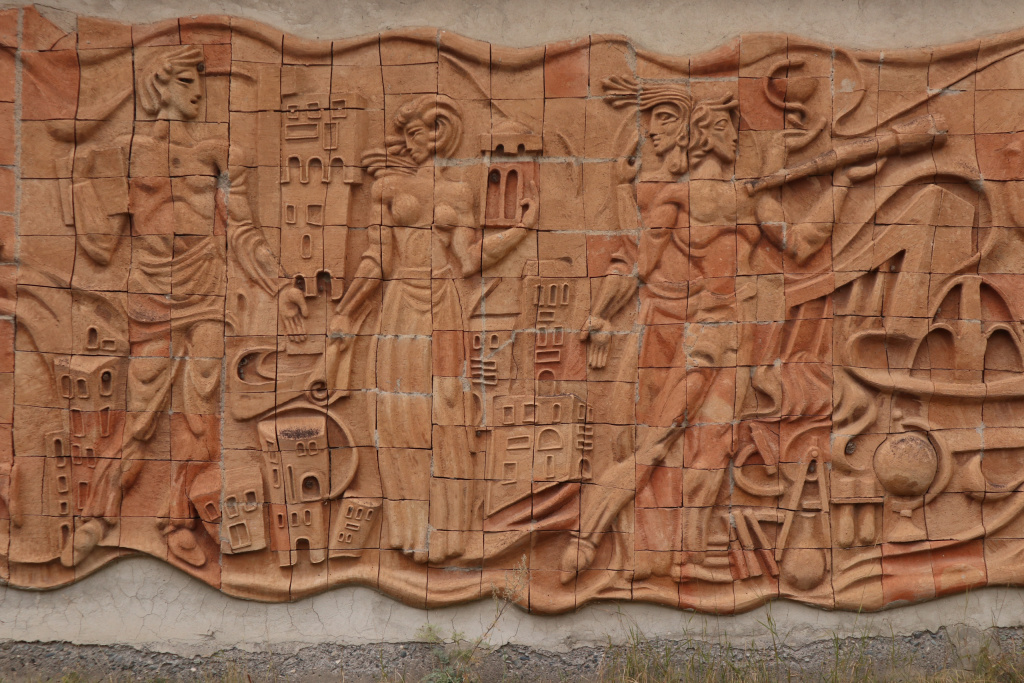

In Georgia, mosaics took on a unique character. In their book Art for Architecture, Georgia: Soviet Modernist Mosaics from 1960 to 1990, Nini Palavandishvili and Lena Prents conducted a survey of mosaics in Georgia, and found that classic Soviet symbols, such as the hammer and sickle or Communist heroes like Stalin and Lenin, are almost never depicted. Instead, as Natali De Pita, the co-founder of the Ribirabo Foundation working to study, preserve, and restore Soviet Georgian mosaics, tells Lossi 36, the iconography frequently relies on “elements of folklore, historical events from the pre-Soviet era, and the work of Georgian literary masters.” In addition, many of these mosaics, created in the second half of the twentieth century, are “geared toward the avant-garde associated with postmodern art.”

“It is simple to follow the history of ideology via mosaics, comprehend parts of daily life, and even comprehend what people believed and dreamt about. Mosaics should be viewed not just as works of art, but also as one-of-a-kind historical documents that depict one or more historical eras in detail using the language of fine art,” De Pita says. “It is probable that the mosaic of the Soviet period embodies the essence of Georgian fine art of the postmodern period.”

One particularly intriguing influence within Soviet mosaics as a whole, but particularly in Soviet Georgia, as Palavandishvili and Prents highlight, is that of the Mexican muralists. Two members of Los Tres Grandes — Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros — made multiple trips to the Soviet Union. Siqueiros even called the work of Zurab Tsereteli, one of Soviet Georgia’s most famous (and controversial) sculptors and architects “comparable to the cream of the oeuvre of Mexico’s monumental artists.” While the iconography may have been different between the two countries, stylistic influence of Mexican muralists is plain to see in a number of Soviet Georgian mosaics.

Yet, even though these mosaics make up a historically and artistically important oeuvre of Georgian artwork, De Pita says that they are rarely given legal protection in Georgia. As a result, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, many mosaics have been neglected, and some even destroyed.

To stem this decay, the Ribirabo Foundation has been working with government ministries and international organisations to create a complete electronic catalogue of mosaics, and build tourist routes in regional areas linking works of art. They have also begun several projects to save and restore mosaics across Georgia, including quite successfully in the industrial city of Zestafoni, turning it into a new tourist hotspot.

There is still much to be done, however. In this article, Lossi 36 will highlight some of the historically relevant and unique examples of Soviet-era mosaics in Georgia, as well as highlight the slow decay of once beautiful pieces of art.

Dreaming of the future: Mosaics emphasising technology and science

Perhaps unsurprisingly, mosaics celebrating scientific endeavours and humanity’s mastery of the elements for their own progress are a common theme throughout the Soviet Union, and the mosaics produced in Soviet Georgia are no different. Generally, however, these mosaics are found within cities, showing the populace a more equal and modern future. They can also be found on buildings related to a relevant industry, such as chemical factories or steelworks.

Within the iconography of progress and labour, space exploration was a specific, recurring motif. Soviet Georgia, like the rest of the Soviet Union, celebrated the achievements of Yuri Gagarin. The first female cosmonaut, Valentina Tereshkova, left less of a mark, however. Palavandishvili only found two examples in which Soviet Georgian mosaic motifs featured a female cosmonaut, despite the ubiquity of the female form otherwise.

The presence of this technological iconography is also notable in that it makes up a large portion of what Palavandishvili has found to be the first Soviet mosaics in Georgia.

Spread throughout the grounds of the former Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy in Tbilisi, now known as Expo Georgia, are five mosaic pieces created between 1961 and 1963 that glorify technological and scientific progress. Focusing on the bright future that awaits the new Soviet citizen, these depictions have much in common with those of East German artist Walter Womacka, whose work “When Communists Dream” became a visual representation of “the historical mission of the working class.”

This vision comes to life in Leonardo Shengelia’s mosaic extending the length of Pavilion No. 8, which depicts the mastery of the Soviet man and woman over scientific progress. In comparison, Guram Kalandadze’s curved mosaic on Pavilion No. 3 focuses on the might of industry, with the new Soviet woman bringing forth all that is good, from new products to the sun itself.

While both of the above works have survived the years quite well, those mosaics on the outskirts of the exhibition grounds have been more or less left to rot. Indeed, Kukuri Tsereteli’s more nature-based motif has entire panels missing from it.

Memorialising the Treaty of Georgievsk: The Russia–Georgia Friendship Monument

Located along the Georgian Military Highway, this monument was erected in 1983 to celebrate the bicentennial of the Treaty of Georgievsk, which established eastern Georgia as a protectorate of Russia.

The anniversary was not well-received in Soviet Georgia. Georgia’s leading underground Samizdat publication Sakartvelo (the Georgian name for the country), dedicated a special issue to the anniversary, emphasising Imperial Russia’s disregard for some of the treaty’s key agreements. In addition, several underground political groups disseminated leaflets calling on Georgians to boycott any celebrations, while the Soviet police arrested “at least ten” youth activists.

The monument itself was ironically not well favoured by Moscow officials either, who did not appreciate the artistic interpretation of the theme of friendship between nations. In mark of their reaction, Palavandishvili writes that the work was not mentioned in any periodical or other media from that time.

Today, however, it is one of Georgia’s most famous monuments and attractions. And in the context of this article, it is notable for being the first time the artist collective of Zuran Kapanadze, Zurab Lezhava, and Nodar Malazonia used the cloisonné method, whereby partitions were used to separate colours in the manner of enamel jewellery, at such a large scale and with a unique material that created a multi-coloured panel, rather than the traditional monochrome. According to Palavandishvili, the artists received a copyright certificate for their invention, which they went on to use in other creations.

Finding beauty in day-to-day transportation: The bus stops and service stations of Soviet Georgia

Appreciation of Soviet bus stops, or ‘bus pavilions’ as they were termed in the specialist literature, has risen in recent years, with a number of photographers cataloguing examples in their specific countries. Georgia is no different, with bus stops often providing some of the best examples of Soviet Georgian mosaics, particularly in more rural areas.

This comingling of function and beauty was part of a broader discussion regarding comfort in urban spaces among Soviet architects in the 1960s. Eventually, it became a government provision that bus stops should be beautiful and reflect a local aesthetic. For example, along the Black Sea resorts, bus stops highlighted marine life and water sports, while in the wine region of Kakheti, local flora, particularly grapes, were featured. Soon, the erection of bus stops became a space for Soviet architects to experiment without worrying about the response from the central authorities.

“We had a committee, an architectural and construction council,” sculptor and artist Zurab Tsereteli told The Guardian. “I suggested that these bus stops shouldn’t be about just a frame, glass, and seating. People should get pleasure out of them. We decided they should be monumental art in space.”

Today, with the face of public transport irrevocably changed, many of these bus stops are slowly falling to pieces. Few are still in use, as inter-city marshrutkas just require the prospective passenger to wave the driver down anywhere along the route. Those that are near cities become places to stick advertisements or to dump trash. Those further away from population centres are re-incorporated into nature bit-by-bit.

Along with bus stops, service stations provided another transport-related area for Soviet artists. One of the best preserved examples of a Soviet Georgian mosaic focused on transport iconography is in Sachkhere, in western Georgia. The entire building is covered in colourful tiles depicting the history of automobiles, abstract wheels bouncing along the walls, and a hand holding aloft a burning torch.

Embracing the natural world: Mosaics celebrating fauna and flora

A number of mosaics produced in Soviet Georgia highlighted the beauty of Georgia’s nature, from its ‘sunny’ disposition to its extensive wildlife.

One of the most famous, and unique, of these mosaics is the Batumi Octopus. This structure, designed by architect Giorgi Chakhava and artist Zurab Kapanadze, was originally opened in the 1980s as a café. It quickly gained renown, both inside and outside of Georgia, even appearing in the popular 1984 Soviet comedy Lyobov i golubi (En: Love and Doves).

Its base consists of a steel grid on eight supports — one for each leg of an octopus — separated by rounded, arched entryways. Aside from this base octopus, various other sea creatures adorn the structure, from the Black Sea’s playful dolphins to twirling starfish. Every inch of the building is plastered in smalti tiles, creating an incredibly colourful and vivid masterpiece.

By the 2000s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the building had undergone severe damage. With the help of a charity foundation, however, restorations were carried out, and it reopened in 2019 as a heritage monument.

While the Batumi Octopus is the most famous of these nature-based mosaics, similar themes can be found throughout Georgia. Not all of them are as well preserved, however.

Mythology in mosaic form: Celebrating Georgian traditions and heritage

Rather than only promoting a modern, Soviet life, a number of mosaics highlight Georgian traditions and the country’s heritage. Grapes are one of the most common symbols spread throughout every region, underscoring Georgia’s more than 8,000 years of wine-making.

National costumes, music, and dance also feature extensively.

In many mosaics, men wear chokhas, woolen coats featuring high necks and rows of felted cases in which rifle cartridges were placed. Each is slightly different based on a man’s origin and his social rank. Women are shown in long dresses, and often wear headscarves. Traditional Georgian instruments such as the panduri (a three-string plucked instrument), the chonguri (a four-stringed lute), and the stviri (a type of flute), are also common.

Surrounding the human beings are often iconic animals popular in traditional myths and fairytales, such as the Colchis pheasant or the red deer.

According to folklorist Zurab Kiknadze, the deer plays a vital role in the Caucasian mythical world. Its horns make the deer the “living embodiment of the connection between heaven and earth,” and it has a “heraldic place” within the Tree of Life that connects each of the three vertically superposed worlds, or skneli.

Looking to the future: Restoration or ruin?

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was an effort to erase the legacy of the Soviet past from visual memory — yet, as Soviet Georgian mosaics did not feature many communist symbols or relate too heavily to communist propaganda, this should not have led to such neglect or wanton destruction. Instead, as Palavandishvili has argued in numerous articles and papers, it is the neoliberal policy of the Georgian government which has caused the most damage. As buildings were privatised, the Georgian state did nothing to regulate the preservation of these historic mosaics.

It is only in the last five years or so that the government, as well as local municipalities, have begun to understand the value in these works of art. Activists and civil society organisations have done the brunt of the work to raise awareness in this regard, being the first to catalogue those mosaics still existing and highlight the damages done.

A new wave of tourists interested in the post-Soviet space has also brought further attention to some of the last remaining remnants of this time, although, as illustrated in this article, the majority of Soviet Georgian mosaics emphasise a broader Georgian history as compared to the sliver of Soviet occupation.

It is necessary for the government to solidify its intent regarding the preservation of these mosaics, assigning the status of cultural heritage in an organised manner rather than waiting for a civil society actor to raise awareness when a mosaic is on the brink of ruin. It is only through a government-led project, which labels these mosaics as historically relevant and worth restoration, that any true change to their status can occur. Further legislation must set a precedent to prevent future destruction; civil society can only do so much of the work.