Europe Votes: What’s Going On? Your Guide to Euro-Elections 2019, Part II16 min read

The EU elections are nearing. For some of you, the polls will open on Thursday (23 May), others have to wait until Sunday. But many of you probably share the same feeling: you’re lost. In our previous article, we tried to introduce you to the exciting world of the European Union institutions. How your vote in European Parliament (EP) elections can influence things, and who you can actually vote for. (Give that article a chance if you still haven’t read it!) This time, we will dive into the hot topics that are dominating this year’s election campaign. And since the EU is ‘United in Diversity’, we have many different regions and 28 member states (yes, the UK included) to cover in this relatively short article, so no time to lose. Put your safari hat on, grab your binoculars – all aboard for the EU jungle!

Does everyone care about the same thing, if they care at all?

The truth is that ever since the first European Parliament elections took place in 1979, voter turnout has seen a downward trend. To be honest, the European Parliament was the unpopular kid sitting at the back of the EU class for a very long time: The institution only had the role of ‘consultative assembly’ up until 1993. And you know what a consultative body does: not much. That changed throughout the 1990s and 2000s, when the Parliament reached political adulthood. With the 1993 Maastricht Treaty, this once useless advisory body became the world’s first and only transnational parliament, elected directly, having a say in important decisions (if you’re interested in how they make decisions: once again, read our previous article).

Sadly enough, this hasn’t changed the political behaviour of most Europeans. However, this time turnout is likely to increase and that may be explained by a simple reason: the world is getting smaller. The EU has gone through a number of EU-shared crises in the last few years (think of the migrant and Euro crises).

Every member state naturally has its own national problems, but the top issues that EU citizens agree must be tackled are actually pretty similar. In fact, 22 out of the 28 member states feel that immigration is the most pressing problem the EU should address while the other six agree that it is terrorism. EU citizens see similar problems but the suggested solutions vary according to the peculiarities of countries and regions. After all, in some countries the EP elections are expected to be the testing ground for national elections, since European parliamentarians are elected from national lists and national political elites hold a tight grip of the EP elections. That is why at this point, we grab our binoculars and turn our attention to the individual stories of the member states and patterns in the different regions of the EU.

[expand title=”CENTRAL EUROPE: BRUSSELS’ ENFANT TERRIBLE“]

When communism collapsed, Central Europe was once again back to… well, the centre. Poland, Hungary and what was then Czechoslovakia transformed themselves within two decades, from an impoverished, totalitarian periphery into stabilised liberal-democracies with boosting economic growth.. In 2004, Hungary, Poland, Czechia and Slovakia joined the EU. The four countries, called ‘the Visegrád’, became known as the Union’s most successful experiment. But for the past couple of years, the winds of change have turned the EU’s brainchildren into the EU’s enfant terrible.

The current European Commission, governed by the centre-right EPP, the centre-left S&D, and the liberal ALDE, has accused Hungary of becoming authoritarian, Poland of ignoring rule of law, and Czechia and Slovakia of being too corrupt. While fueling the nationalist discourses in this region, the Commission hasn’t actually been able to influence national policies in Central Europe considerably. This is partly because Central Europeans are big in number, so they can block a lot of proposed punishments towards themselves and their neighbours. But the biggest obstacle for the Commission is that most governing parties in Central Europe belong to the alliances governing the European Commission. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz belongs to the EPP, Czechia’s ANO 2011 is allied with ALDE, and Slovakia’s Direct Social Democracy is part of the S&D.The latter government has been notoriously unpopular recently for corruption and other crime-related scandals (most notoriously, the murder of a journalist). Only Poland’s governing party, PiS, is part of the European opposition, belonging to the ECR: an alliance with traditionally more Eurosceptic language, although strategically distancing itself from Brexit-like scenarios. The ECR may turn out to be the real winner of Central Europe in the upcoming elections. In Slovakia, multiple small parties (SaS, Ol’aNo and NOVA) all joined the ECR, which means that this alliance will likely be the biggest Slovakian alliance after May. In Czechia, the ECR is competing with the Pirates for a comfortable second spot. Even in Poland, where the entire opposition (from socialist to conservative-right) has unified under the EPP, it is likely that ECR’s PiS will remain victorious. Only Hungary is ensured to strengthen the EPP. But for how long? Tensions between Prime Minister Orbán and the EPP continue to worsen. Recently, Orbán even dropped his support for the EPP’s presidential candidate, Manfred Weber. Meanwhile new pro-European parties (like the Czech Pirates, Poland’s Spring, and Progressive Slovakia), which do not belong to any alliance yet, are likely to gain many seats too.

Even more than other regions of the EU, the eastern member states are particularly concerned with the migration crisis. Unlike in Western Europe, it is difficult to find many Central European politicians who are explicitly in favour of allowing refugees or other migrants into the country.[/expand]

[expand title=”THE BALKANS: PROTESTS, CORRUPTION AND MORE PROTESTS”]

Roses are red, the Balkans are a mess; or so goes the common wisdom. That’s not entirely fair: most of the Balkan countries, including the non-EU countries (like Serbia and North Macedonia) have undergone significant democratisation and seen economic growth in the past years. But it is true that Balkan politics remain unstable compared to any other region of the EU. And yet, this has not damaged the EU’s governing elite. So far.

Romania has seen widespread protests against the government since 2017, when an emergency decree pardoning corruption-related offences was passed. In the midst of the ongoing turmoil, Romania, at the beginning of 2019, was inaugurated as the president of the European Union Council. During the ceremony hundreds joined pro-EU and pro-rule of law protests against the government. Sounds nice to the Europhile ears, right? Well, meanwhile the government uses anti-Brussels rhetoric for the first time in Romanian politics. This included a tone of defiance by the Prime Minister during the EP hearings last year when he spoke of fake news regarding the rule of law in Romania and a ‘lack of respect for the Romanian people’.

Speaking of protests, Bulgaria has been another hotbed of political and social unrest. Bulgaria is home to the highest levels of poverty and income inequality among the EU member states, and corruption amounts to 14% of the country’s GDP. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that people feel disrespected by their government, mistrust their institutions and that national issues will dominate the EP elections. Many share the opinion that the EP elections ahead will be a testing ground for the popularity of the current government, so the results can lead to early elections.

The latest addition to the club, Croatia, is also having a ‘colorful’ election campaign. There are new actors in the game at different ends of the political spectrum. One is the Amsterdam Coalition, formed by the liberal opposition parties, which calls for Croatians to vote for a “European Croatia”. The other is a new populist, Eurosceptic party, Živi zid; calling for the people to choose between “servility and freedom”. The former is in coalition with ALDE, the latter with the Five Star Movement of Italy, and both are expected to gain one seat each. Such representation!

Greece continues to be an unstable political zone too. But more about that later, as the Greeks are facing somewhat similar problems as their fellow Mediterraneans. And Slovenians? To the annoyance of many ‘Balkanese’, most Slovenes don’t like to be part of the Balkan club. From a political point of view, Slovenia seems an island of stability, detached from Western Europe’s far-right and the Balkan’s corruption protests. Slovenia’s only challenge for the EU’s elite comes from the left, in the shape of the European far-left’s (GUE) presidential candidate and Bosnian-Slovenian Marxist actress Violeta Tomic.[/expand]

[expand title=”THE BALTICS: SANDWICHED BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE UNION”]

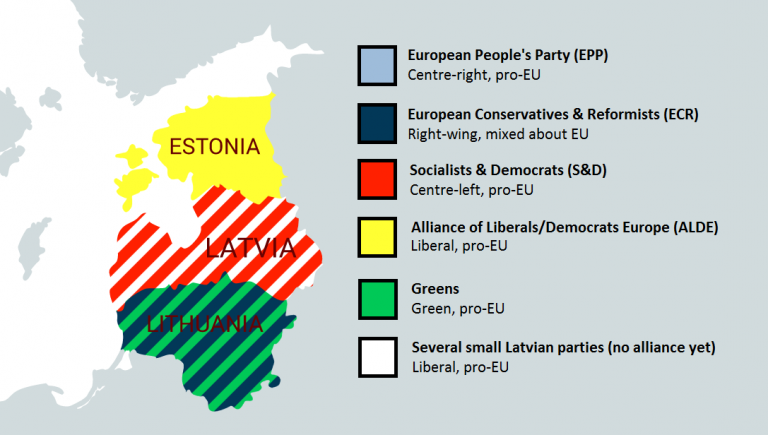

30 years since waving goodbye to the Soviet Union, the ‘‘Russian problem” is still a lingering issue for the Baltic club. There are two dimensions to the problem: 1. All three countries have a big Russian-speaking minority; therefore, Eurosceptic disinformation campaigns by Russia find very fertile ground 2. Well, Russia annexed Crimea and is increasingly militarising right next door. But the three countries also share a similar social problem: inequality. Although the Baltic states have seen speedy economic growth in the past two decades, all three rank above the EU average in income inequality – with Lithuania ranking second highest in the Union. Although the older and more established parties in the Baltics are expected to gain majority of seats in the EP, new parties on the left and right of the political spectrum are also fairly popular. It seems like the painful difference between the center and periphery make the people feel left behind by the establishment and look for alternatives; hence the glide towards the Eurosceptics or Greens.

At the moment, Latvia has a particularly fragmented political scene with many small, non-affiliated parties that are expected to gain one seat each. The recent feud between the government and Riga’s Russian mayor that ended with the ousting of the mayor from the office due to corruption allegations is expected to work up ethnolinguistic tensions and find high resonance in the EP elections. Also worth mentioning is that Latvia doesn’t seem to have jumped on the Eurosceptic train in this campaign.

At the beginning of this year, international media put their party hats on and celebrated Estonia electing its first female prime minister, the leader of the Reform Party, Kaja Kallas. Everyone projected that the Reform Party, who pulled a surprising win in the March 3 vote, would form a coalition with the Center Party that came second in the race. *Spoiler alert* – It didn’t happen. The coalition was formed between the Center Party and the fierce Eurosceptic, anti-immigrant, far-right EKRE, who more than doubled its votes and became the third biggest party in the parliament. In a nutshell, things have been turbulent ahead of the EP elections. How did EKRE get here and why does anti-immigration rhetoric work in a country that has taken in only 206 refugees, 80 of whom have since left ? The answer is in the first paragraph: relative poverty in rural Estonia and income inequality. In her speech at the opening session of the parliament, President Kersti Kaljulaid admitted that there is a “crisis of values” and that Estonia “has been inept in balancing society”. So the anti-immigrant rhetoric seems to be the tip of the anti-establishment iceberg. EKRE is with Matteo Salvini’s alliance ENF in the EP and is expected to gain one seat.[/expand]

[expand title=”THE MEDITERRANEANS: A EUROPE OF CRISES TURNS AWAY FROM THE PAST”]

Crisis after crisis, the Mediterranean has been on a shaky boat in the last five years of the Juncker Commission (the current European ‘government’). The damage of the Eurocrisis can still be felt in most economic sectors of the southern member states (perhaps Portugal excluded, or is it?), whereas the migrant crisis has not been completely solved either.

Interestingly, although the problems in Southern Europe seem to be of a shared nature, the preferred solutions differ drastically. Still, the political trend can be summarised in one sentence: Those who haven’t been governing in the last years are rising in popularity.

That means that the Iberian countries, Portugal and Spain, have made a socialist U-turn from their centre-right years dominated by EPP-aliated parties. In Italy , it means quite the opposite: having been governed for a few years by S&D-allied social-democrats, the country is now turning to Salvini’s nationalist far-right party Lega (part of the ENF).

And Greece? Due to particularly harsh conditions during the Euro Crisis, Greeks already voted in 2015 in majority for the far-left marxist party Syriza (part of GUE). But the ongoing migrant crisis, as well as the painful scars from the economic collapse a decade ago, have led the population likely to turn back to the good old pre-crisis elite: Nea Dimokratia (part of the centre-right EPP).

With or without new political movements, the South is likely to face two old headaches in the upcoming five years: the austerity problem and the migrant problem. Most Southern parties have agreed already for years that the current economic system in the EU can no longer continue. The current austerity-based policy of Brussels forces the Mediterraneans to limit their debts, while the southern countries simultaneously need to go into more debt in order to invest in economic sectors. Most northern member states (including Germany and the Netherlands) aren’t so enthusiastic to drop the austerity policy, as they fear it will allow the southern countries spend their money irresponsibly. Additionally, for the last few years, Mediterranean governments have urged fellow EU member states to take a fair share of the migrants and refugees arriving on their beaches. For now, however, most non-southern member states have not fulfilled their quota of migrants (Sweden and Germany being the exceptions). Eastern member states were particularly unwilling to help out the Southerners.[/expand]

[expand title=”THE NORDICS: RETURN OF THE LEFT?”]

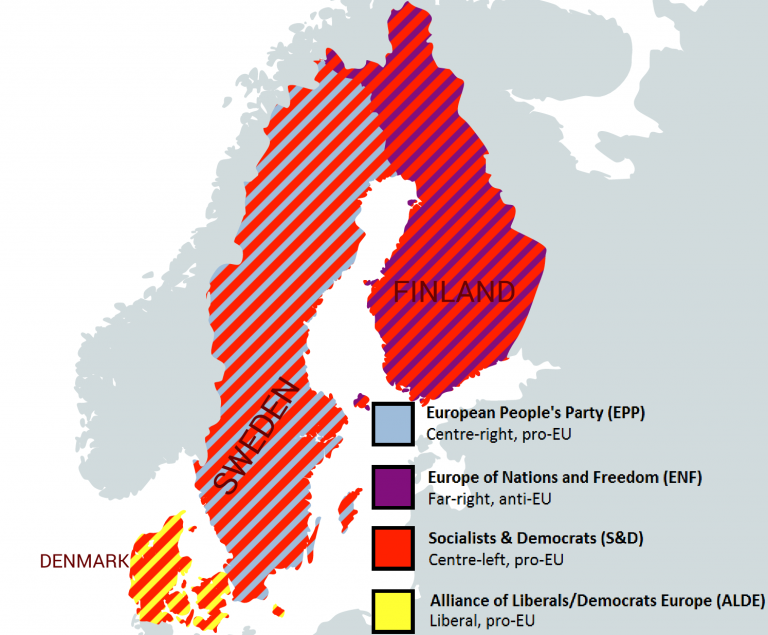

Why didn’t we count the Nordics as Western Europeans? Because unlike their Western colleagues, the Nordic socialists and social-democrats (most of them allied to the centre-left S&D) are enjoying relatively high popularity. Leftist successes may not be an historical rarity in Scandinavian governments, but they are today in Europe. That doesn’t mean that they are the only potential victors. As elsewhere in Europe, anti-EU and anti-immigration formula forecasts success for the upcoming elections in all three countries. It is fair to say that the EP elections campaign in the North is centered around migration and environmental policies.

Finland is a little too busy with its national politics as the general elections just took place this April. At the time of writing, talks for coalition formation are going on, so the EP elections are left in the shadow of national elections and the EP elections are expected to resonate the results of general elections.

In Denmark and Sweden, the Social Democrats are leading according to the polls but their lead is narrow. In our previous article, we mentioned that social democrats are in an overall crisis in Europe, and perhaps this can be best felt in Scandinavia as the historic fortress of social democracy. What has changed? Social democrats inability to transform and deal with growing inequalities and immigrations issues have given rise to populist parties. However, the Danish Social Democrats adopted a more restrictive immigration policy last year, controversially calling for a reduction in the number of new immigrants and establishing reception centers outside of Europe. While some would argue that the package is a sellout of their principal values, allowing the far-right to set the tone on immigration, others claim the package finds international solutions founded in the roots and ideology of the party. It might be working, given that opinion polls both for the EP and national elections show a lead for the Social Democrats.[/expand]

[expand title=”THE WESTERNERS: THE WEST STILL HAS THE FINAL SAY (FOR NOW)”]

‘European news’ or ‘European politics’ often equal ‘Northwestern European things’ and this can be rather weary for the rest of the club. But whether you like it or not, the West is still the economic and political heart of the Union.

Ever since the end of World War II, France and Germany have been called the axis of European integration. And to a great extent this is still true today. The UK, in that sense, has always been the exception in the conviction that European integration is necessary. With one hesitant leg in the EU and the another one firmly in the ocean, the UK has always been the counterbalance to Franco-German cooperation. With Brexit likely to happen, the Franco-German axis has often expressed its hope for ‘a new beginning’. Read: an EU without those British roast beefs (freely translated from French).

While the Britons are planning to distance themselves from Paris and Berlin, a new antagonist has popped up in the last decade, and it is getting bigger each election. More challenging than London, the new opposition comes from within. More Western Europeans are turning to Eurosceptic and anti-EU parties. As a result, France has found itself in a rat race between an increasingly unpopular president Macron (the biggest party of the liberal ALDE) and Marine Le Pen’s far-right movement (the biggest party of the nationalist ENF). Belgium and the Netherlands are experiencing popular nationalist movements (both part of the mildly eurosceptic ECR), which form a powerful challenge vis-à-vis the liberal elite of the Benelux. Although German chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU (the biggest party of the EPP) is roaring in more stable weathers, it can no longer take its popularity for granted, as it could have five years ago.

Already for the second election in a row, the biggest losers in Western Europe are likely to be the social democratic parties (S&D). Only Austria is likely to experience a moderate centre-left victory, a success that may be caused by a long absence of social-democrats in Vienna.

Although the lasting effects from the Euro crisis seem long gone in Northwestern Europe, and the migrant crisis has stopped being a visible trouble to this part of the continent, the ‘Eurosceptic spring’ is far from over. While the EU’s existential crisis has been successfully limited in recent years, there isn’t much time to rest – both for supporters and opposers of the EU. The West, as the economic and political heart of Europe and as the source of Brexit, Le Pen and the EU itself, will continue to be the battlefield of this combat.[/expand]

Who are you going to vote for?

Still not sure who to vote for? Here are some helpful sites: Based on you political convictions, his EuroVote test tells you which European alliance to vote for. Your vote matters presents how your favourite parliamentarians have voted on key-decisions in the past years while the MEP ranking reveals how often they voted and whether or not they showed up at all.