New filmfestival to showcase Eastern European Cinema5 min read

At the end of this month, Glasgow is getting its first-ever Eastern European film festival. Between 27 September and 13 October, the organizers behind Samizdat will screen movies from all over the former Eastern Bloc at the city’s Centre for Contemporary Arts and online. We talked to the Samizdat team about Eastern European cinema and about why they wanted to organize an Eastern European film festival now.

What is the idea behind Samizdat?

From the very start, we thought of Samizdat as a way to present the diversity and complexity of a cinematic culture as aesthetically and culturally rich as it is intensely political. ‘Samizdat’, which translates as ‘self-publishing’, stands for the print and dissemination of forbidden and censored text and art in the former Eastern Bloc. As curators and exhibitors, we hope to play a similar role to a supplier of samizdat – to serve as a gateway for what is surprising, foreign, unfamiliar, opaque, or othered. To that end, we have curated a varied programme with films from Serbia to Tajikistan presenting a myriad of beautiful and exciting stories.

Just like in the Eastern Bloc, today we see that filmmakers in some Eastern European countries are threatened persistently by state censorship and political repression. If our festival continues to grow, we would like to provide a platform for filmmakers who are facing and confronting such challenges.

How did you come up with the idea to organise an Eastern European film festival in Scotland and why now?

The idea for the festival came during the summer of 2021. While there are several UK festivals dedicated to the cinema of disparate countries and regions – for instance, Kinoteka Polish Film Festival and the London Georgian Film Festival – very few festivals focus on the larger Eastern European and post-Soviet regions.

Of course, there is New East Cinema, which is run by a London-based curatorial collective, and our partner for the festival, an online streaming platform called Klassiki.

However, knowing that no such initiatives existed in Scotland, we wanted to fill this gap to bring greater awareness to Eastern European cinema – both past and present – to a Scottish, British, and wider Western European audiences.

We also believe that an Eastern European film festival is a good way to advocate for Eastern European diasporas living in the UK – who often face significant challenges with social and institutional discrimination and racism. The rise of nationalism and xenophobia following Brexit have exacerbated the situation even further. Given these issues, our hope is to make Samizdat a place where Eastern Europe is represented fairly and open-mindedly. We want to be a platform for intercultural interaction for diaspora groups.

As we were working on Samizdat, Russia escalated its invasion of Ukraine to a full-scale war. To express solidarity, we have curated a special strand of Ukrainian cinema, featuring five films and two special events. The strand intentionally includes a mixture of films that focus on the war and those that do not, so as to avoid defining Ukraine exclusively through the Russian invasion.

Who is behind the initiative?

Our organisers have different nationalities and backgrounds. Most of us are PhD students and film industry workers who hold some degree of expertise in Eastern European cinema, hailing from Russia, Ukraine, the Chuvash Republic, England, and Scotland.

For someone who is not familiar with the region, could you name three must-see Eastern European movies?

Andrew Currie, Festival Director

For someone new or unfamiliar with the region’s cinema, I would personally recommend films from the 1920s and 1930s, during the golden age and rise of socialist realism in Soviet cinema. There are films like Battleship Potemkin (1925), Mother (1926) and Chapaev (1934), which are probably familiar to most cinema-goers, that have had a massive influence on the course of both Soviet cinema and worldwide cinema.

My personal pick from the interwar period would be Earth (1930) by Alexander Dovzhenko, a Soviet Ukrainian film about the impact of collectivisation on Kulak landowners during Stalin’s first five-year plan. Apart from being a remarkable product of its era, Earth speaks to the plight of many people who have faced or now face, state oppression and the collective ability of people to rise up against their oppressors. This simple message, however, is made more poignant by some of Dovzhenko’s cinematographic techniques, from his close-ups of several peasant characters and the long silences in between — highlighting their frailty and suffering in the face of collectivisation — to wider shots of Ukrainian landscapes that are rich with life and vitality.

Misha Irekleh, Head Curator and Accessibility Manager

I would recommend Terra – a 2018 documentary short by Julia Kushnarenko. This film sheds light on a completely erased part of Russia: the indigenous peoples of Siberia’s North and the ecocide they face at the hands of the Russian state. The Nenets (pronounced closer to Nenz) people of Yamal have always lived by nomadic reindeer herding. Their traditional lifestyle and the right to roam through Yamal’s wilderness are officially protected by the state. Unfortunately, the Nenets’s land is full of hydrocarbons. In its greed, the Russian state is wrecking Yamal’s vast but fragile ecosystem and robbing Nenets and Yamal’s other indigenous peoples of their way of life. To make matters worse, profits from hydrocarbons stolen from indigenous lands are being used to fund Russia’s war machine in Ukraine, Syria, and elsewhere.

Ilia Ryzhenko, Fundraising Manager and Curator

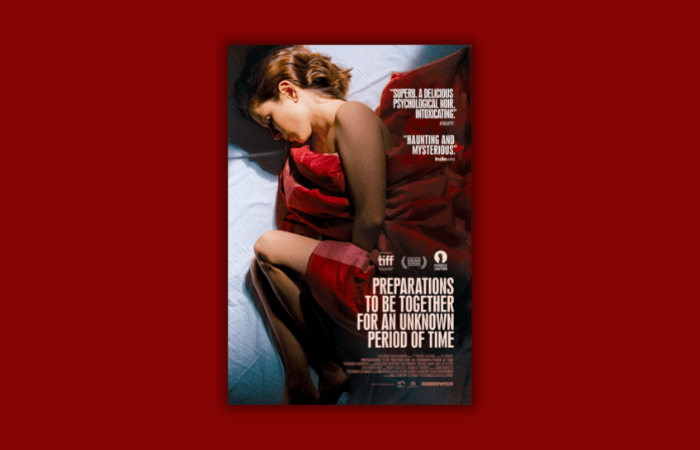

There is a Hungarian film that came out quite recently called Preparations To Be Together For an Unknown Period of Time (2020) by Lili Horvát that I consider an absolute must-watch for everyone who is a fan of the mystery of Christian Petzold’s Undine (2020) or the listlessness of early Tsai Ming-liang. An accomplished Hungarian neurosurgeon moves back to Budapest from the States to meet with a man she fell in love with at an international conference – but he doesn’t recognise her at all. It’s a beautifully confusing story about losing one’s grip on reality and memory, but what’s most notable for me was the way in which it went about portraying this sense of confusion. In a manner quite characteristic of Eastern European cinema, it remains enigmatic throughout, always suggestive but never too translucent or too opaque. Certainly one of my favourite films of the past two years.

The organisers behind Samizsdat will screen movies from all over the Eastern Bloc at Glasgow’s Centre from Comteporarty Arts between 27 September – 1 October and online on the streaming platform Klassiki between 27 September – 13 October. View the full programme here.