Colonial Pasts, Contested Futures: the disparate legacies of Soviet architecture in Estonia9 min read

In 1940, after a series of ultimatums and coercions, the territory of Estonia was annexed by Soviet forces. Though Estonia would be taken by the Nazis in 1941, three years later the Red Army recaptured the country and fully incorporated it into the Soviet Union. In the subsequent decades, a massive Sovietisation project took place as the Soviets attempted to strengthen their ideological stranglehold over the new Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Soviet occupation would prove to have radical consequences for urban space in Estonia. Westward migration and industrialisation were accompanied by dramatic residential expansion, while public buildings were now constructed to represent the communist principles of the state. Following the collapse of the USSR in 1991, efforts were made to decommunize the Baltic nation. But as in much of the post-Soviet space, the legacy of the Soviet period lingers unignorably through its impact on the country’s architecture.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has yet again placed questions regarding the USSR’s colonisation of Estonia at the forefront of public debate. For example, should the war in Ukraine force a change in the memorialisation of the Soviet period? How does Estonia’s post-Soviet generation internalise its country’s colonial past? In an attempt to find answers, I travelled across the country to photograph some of Estonia’s best Soviet-era architecture and interviewed Triin Ojari, architectural historian and Director of the Estonian Museum of Architecture.

Competing Interpretations of Soviet Symbolism

Tallinn’s gothic centre and cobbled streets certainly do not resemble the stereotypical images of a post-Soviet capital, but Soviet relics are there to be found for those who go looking. A short bus ride from the city centre sits the Maarjamäe Monument, a masterpiece of modernist sculpture built in the 1960s. A series of sloped paths carve Maarjamäe into the hillside, while a 35-metre-high obelisk overlooking the Gulf of Finland surrounded by low-set concrete pyramids serves as the centrepiece of the site.

Maarjamäe Monument

Maarjamäe Monument

“The site of Maarjamäe is particularly interesting,” Ojari explained. “It neighbours the Museum of Estonian History and a garden of crumbling statues of Lenin and Stalin. It is also a burial ground of German soldiers who were killed during the occupation in 1943.”

Most interestingly, though, the Maarjamäe Monument shares its location with the Memorial to the Victims of Communism, opened in 2018. I asked Ojari whether it was a politically driven choice by the authorities to place the new memorial at Maarjamäe. “Obviously there wasn’t a sufficiently large area in the city itself…but it was a little bit of a surprising decision”.

In many ways, the site of Maarjamäe serves as a microcosm of Estonia’s turbulent twentieth century. The state of the monument is perhaps indicative of broader public opinion towards the Soviet period: many of the paths are overgrown, while vandalism and poor maintenance have dictated that much of the monument now sits behind barricades.

Linnahall, in the centre of Tallinn, is another case in point. One would be forgiven for thinking that the structure is some kind of bunker at first glance: it is almost completely windowless, entirely constructed from concrete, and is just 3-4 storeys high despite commanding a sizeable share of central Tallinn’s seafront. Built to showcase cultural events during Tallinn’s hosting of the yachting regatta at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, Linnahall houses a 4,000-seat theatre and numerous administrative spaces.

Linnahall, Tallinn

Linnahall, Tallinn

Linnahall was highly innovative in its design and architectural principles. Indeed, according to Ojari, Linnahall was intended to transcend the boundary between coast and city. “It is quite an interesting piece of architecture in how it tries to connect the centre with the waterfront. It’s a huge public space…because of the terraces and staircases on the roof, you feel this connection.” The international community evidently agreed: in 1983, its Estonian architect, Raine Karp, won an award from the International Union of Architects.

In spite of its decorated history, Linnahall has fallen out of favour with much of the Estonian public. “In the last few months since the war, a lot of real estate developers have argued in favour of demolishing it because it somehow destroys the view from the centre to the sea,” Ojari said. Linnahall has struggled on in a state of limbo since its main concert hall was closed in 2010, though its accessible exterior means that it continues to be a well-utilised space by Tallinn’s youth and graffiti artists.

It is tempting to look to politics or aesthetics for an explanation of why Soviet structures like Maarjamäe and Linnahall exist in such a state, but the reality is more complicated. On the one hand, they are interpreted by those who lived through the period as reminders of the Soviet’s brutal oppression. But on the other hand, these structures were mostly built by Estonian architects; much of the Estonian generation born after 1991 therefore consider these buildings as important expressions of national heritage incongruous with the period’s colonial zeitgeist.

“There were very few Russian architects in Estonia during the Soviet period,” Ojari told me. “Despite norms in housing, Moscow didn’t dictate aesthetically.” Indeed, Estonia’s Finno-Ugric heritage has given it a strong modernist tradition – a tradition that survived the Soviet period. Notably, both Maarjamäe and Linnahall feature little in terms of staunch Soviet symbolism and sloganeering. Ojari sees this as both a blessing and a burden: “though they are mostly free from Soviet symbols, this perhaps makes them easier to appropriate.”

The Regeneration of Community Space

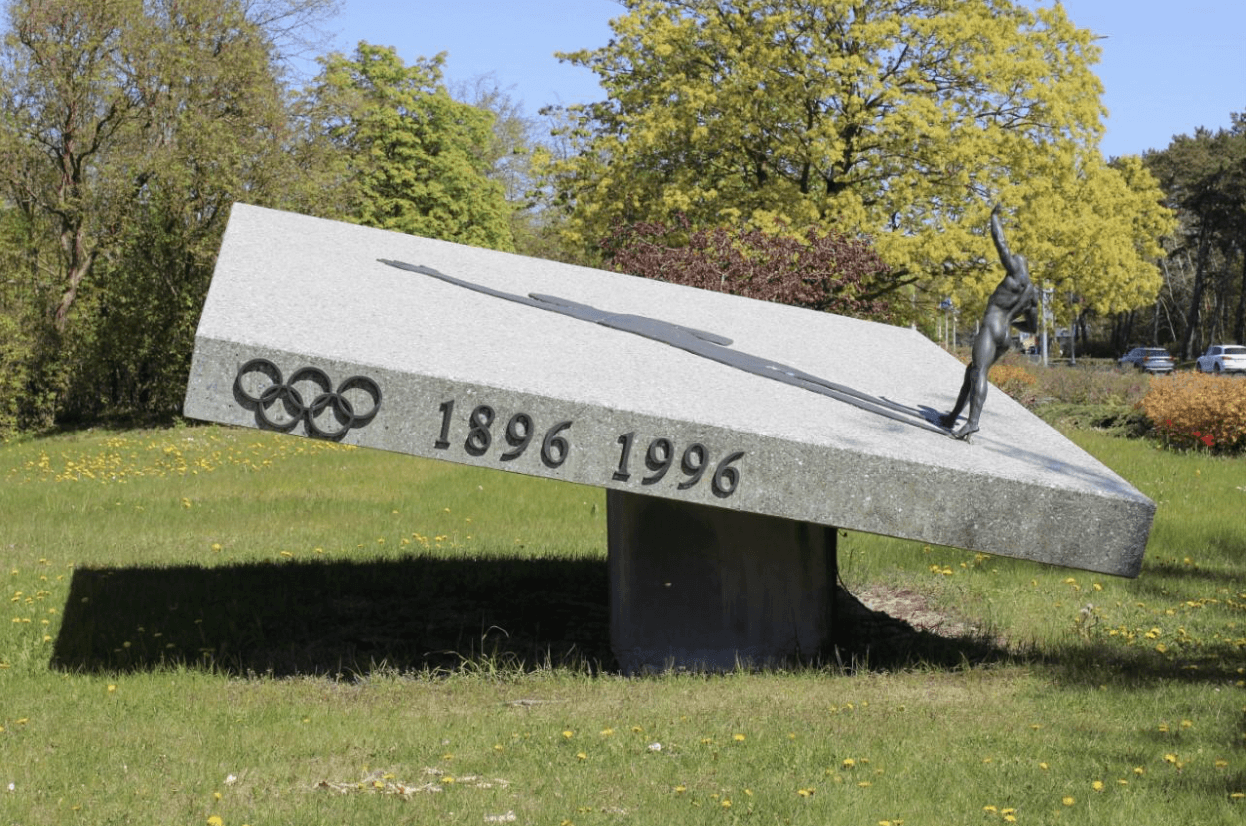

However, Soviet-era structures that have fallen into private hands have tended to fare much more favourably since 1991. Ojari attributes mostly fond memories of the Olympic period to this phenomenon: “the Soviet period [of architecture] was all about showing off,” Ojari said. “During the Olympics, a lot of new things arrived in people’s daily lives as a result.”

Olympic Hotel in Tallinn

Olympic Hotel in Tallinn

Indeed, the coincidence of the Moscow Olympics with the modernisation of Estonia has shored up the future of many structures constructed for the games. Take the former athletes’ residences in Tallinn, for instance. In notable contrast to the state of Maarjamäe and Linnahall, these spectacular sloped, brutalist apartments have been granted a new lease of life as accommodation for the Olympic Hotel, providing guests with sunlit balconies and unspoiled views of the Gulf of Finland.

Another example is the Annelinn microdistrict in Tartu, Estonia’s second largest city. Ostensibly, there is nothing particularly special about Annelinn. “Annelinn is one of those typical Soviet period microdistricts,” Ojari agreed. It is true that such microdistricts are mostly homogenous in their design and can be found everywhere in the post-Soviet space. In Estonia, the situation is not much different: “a factory in Tallinn produced almost all of the panels, and the Estonian Project, led by local architect Mart Port, designed the majority of the microdistricts.”

Annelinn district in Tartu

Annelinn district in Tartu

Many microdistricts in the post-Soviet space have been neglected by their governments as expensive maintenance has fostered a preference for demolition or new-build apartment complexes. During my visit to Annelinn, however, I was overwhelmed by a palpable sense of civic pride. Indeed, EU funding and private ownership both seem to have brought the microdistrict concept to its full potential: rejuvenated green spaces, water features, and public buildings such as libraries serve the local community, while frequent transport connections on the periphery provide a reliable lifeline to Tartu’s chic centre.

Preservation and Decline in Estonia’s Borderlands

Nevertheless, away from the main urban centres, the uncertain fate of Soviet buildings in Estonia becomes clear once again. In the coastal town of Sillamäe, which was closed during Soviet times for its uranium refining facilities, an awkward marriage of decline and preservation acts as something of an architectural metaphor for the rest of the country. Located near the Russian-border city of Narva, a large proportion of Estonia’s Russian speakers – which constitutes approximately 24% of the total population – reside here and in the surrounding regions.

Industrial district, Sillamae

Industrial district, Sillamae

Stalinist Promenade, Sillamae

Stalinist Promenade, Sillamae

Palace of Culture Garden, Sillamae

Palace of Culture Garden, Sillamae

Sillamäe is known among Soviet architecture enthusiasts for its Stalinist beach promenade and neighbouring palace of culture. It is evidently a site of pride for locals, judging by one starry-eyed elderly man’s description of the area as he pointed me in its direction and the fact that its gardens were being renovated when I visited. But away from the main street, signs of decline are evident. Many of the buildings’ facades are falling away, and when heading towards the towering smokestacks on the edge of the town, abandoned industrial structures become quickly abundant.

“Narva and Sillamäe are almost totally different regions, as you can imagine. They are basically only Russian speaking. All the locals were deported after the Second World War.” This status on the relative periphery of Estonia has left the region with socioeconomic issues and little time for public debate about architectural preservation. Indeed, Narva has the highest unemployment rate in Estonia at 12.4%, with the youth particularly affected. “People don’t have the money or interest in reconstructing urban areas…it is more of an economic problem than an ideological one.”

Embracing History in the Post-Soviet Era

Soviet buildings clearly occupy a liminal space in contemporary Estonia. Russia’s war in Ukraine has reignited questions about the legacy of the period, and the mixed state of Soviet architecture – though certainly not the only point of contention – is indicative of a society in which questions of historical memory are very much unresolved and divided along generational lines. With such tangible and lasting impacts on everyday life, though, it is no surprise that architecture remains at the forefront of debate as Estonia grapples with its colonial past.

Despite this atmosphere of uncertainty, Ojari envisions a positive future. “The younger generation doesn’t have such feelings of anger towards the Soviet period…they judge these buildings by their architectural quality, not by the ideology under which they were built.” Ojari is right: free from lived experience of the period, Estonia’s post-Soviet generation widely interprets the nation’s Soviet past through a lens free from politics.

Many post-Soviet Estonians also increasingly recognise that the architecture spawned by Soviet colonisation was a unique historical phenomenon, and it is precisely this combination of open-mindedness and appreciation that is beginning to turn the tides in favour of preservation. “These buildings are different – today, nobody would build something like Linnahall. They are crazy, even absurd, in a sense.”

This shift in public opinion owes much to the work of historians like Ojari and the Estonian Museum of Architecture. Meanwhile, Tallinn’s Olympic Hotel and Tartu’s Annelinn microdistrict demonstrate that Soviet buildings can become fully integrated into local communities regardless of historical connotations. As the war in Ukraine throws the legacies of Soviet rule into question across the post-Soviet space, in Estonia – a country with a particularly fraught relationship with its colonial past – the future of Soviet buildings looks unexpectedly bright.