How Georgia’s youth mobilised against a controversial “foreign agent” law9 min read

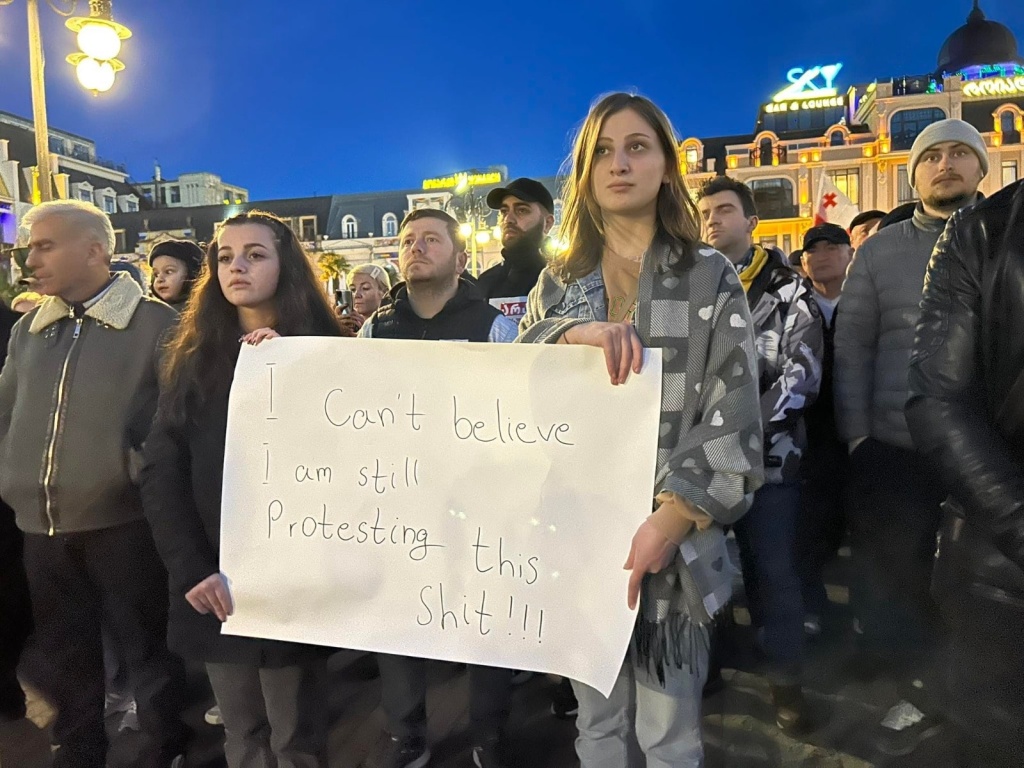

Last week, thousands of Georgians demonstrated in front of the Parliament on Rustaveli Avenue, the vibrant and busy street in the heart of Georgia’s capital. Wrapped in Georgian flags and the blue and yellow colours of Ukraine, the protesters played music and chanted against the government, in support of the Ukrainian people, and for Georgia’s European future. University students organised themselves on campus to attend the rallies, and groups of friends met on Rustaveli. The scale of the protest took many observers by surprise, and was largely made possible by the active participation and mobilisation of Georgia’s youth.

The month prior, People’s Power, a more extreme splinter of the governing Georgian Dream (GD) party, submitted a draft law to label organisations as “foreign agents” if they received more than 20 percent of their funding from abroad. Immediately, the proposal received criticism from various opposition parties and civil society organisations. As the governing party moved forward with the law, bringing up the first reading by two days, large-scale protests erupted in front of the Georgian Parliament in Tbilisi. After two nights of protest and more than hundred of arrests, GD announced they would “unconditionally withdraw the bill.” Following a third night of demonstrations, GD officially voted against the bill in Parliament and released all those detained.

Students become one face of the protests

On 3 March, students at Tbilisi State University (TSU), the country’s oldest institution of higher learning, withdrew from the courses of GD member Nikoloz Samkharadze over the draft law. He had chaired the joint session held on 2 March between the Parliamentary Committees on Defense and Security and Foreign Relations to discuss the law, and came to be regarded as one of the top figures related to said bill.

“He taught us about the importance of Euro[pean] integration for Georgia and now he was supporting the law, which directly contradicts the Georgian constitution and undermines the country’s European and Euro-Atlantic aspirations,” Elene Mikanadze, a student at TSU, said. “Immediately following this incident, we knew the students would be more engaged in the protests now than ever.”

Shortly after, a group of students coalesced under the movement “Students Against the Russian Law” to condemn both Samkharadze’s actions as well as the draft law. “As our professor became the face of this ‘Russian law,’ our movement with all the students became the face of the protests. It was one of the rare occasions when the demonstrations were not led by political parties but by young people and the NGO sector,” Mariami Japaridze, a student in her last year of the International Relations programme at TSU, said.

By 8 March, students were organising a march from Ilia State University and TSU to Parliament, as well as calling for a campaign of civil disobedience against the draft law. “I think students were the main driving force for these protests and the main reason they were successful,” Luka Chitiani, one of the co-organisers of the student protest at TSU, observed.

Mikanadaze attributes the large student presence to the fact that they understood what was at stake regarding the draft law.

“We knew about the evolution of [a crackdown on press freedom] in Russia from 2012. The ‘foreign agent’ law would start the expansion of authoritarian control,” Mikanadze argued. “Nowadays, numerous students are engaged in youth work and they are representatives of different non-governmental organisations. The students in said organisations help minorities, people with disabilities, abused children, and women — those who are at the highest risk of being left defenceless through this law.”

Protests spread across the country

One facet of the protests was its decentralised nature, which saw a number of demonstrations emerge spontaneously across Georgia. Both Batumi and Kutaisi saw large-scale protests, while a broader strata of society, including habitually neutral football clubs, also expressed support for the protests. The parallel protests for International Women’s Day on 8 March, a public holiday in Georgia, also increased the participation, with the two protests often merging.

In Batumi, students made up a large contingent of the protesters, organising a march from Shota Rustaveli State University to Europe Square. Various civil society groups in the city united, and on 8 March, women joined the general march.

According to Mariam Mutidze, a Batumi-based reporter, “people know that both [the media and NGOs] are very important for Georgia to build a strong, democratic, European country. I think the Georgian people, and especially Georgian youth, won this game.”

Kutaisi saw a similar response, with citizens spontaneously taking to the streets, growing several thousand in size after 8 March. “Young people, organisations, public figures — their voices were heard loudly,” local activist Akaki Saghinadze said. That day, Saghinadze’s house was spray painted with accusations that he was a spy.

The decentralised nature of the protests, which saw demonstrations in several major cities, contributed to the protests’ success. While the ruling party tried to position itself and to create suitable conditions for the upcoming parliamentary elections next year, the wide mobilisation across the country demonstrated the unpopularity of the law, upping the pressure on the government to withdraw the proposal.

The government crackdown on peaceful demonstrations

The government was quick to respond to the protests, using riot police equipped with pepper spray, water hoses, sound machines, and rubber bullets to disperse demonstrators in Tbilisi.

“I was equipped with goggles and a mask. Unfortunately it didn’t help me,” Salome Dzvelaia, a Tbilisi-based artist, said. “I found myself alone in front of the special police. I started shouting, repeating that they are traitors, after which they threw gas in my face. I could not see anything and I was suffocating.”

Journalists were also specifically targeted by riot police. “The squad hit me in the face. This happened 1-2 seconds after Nestan, next to me, yelled ‘We’re the press!’ and I had a press card hanging,” wrote Netgazeti‘s Buba Gvadzabia on Facebook. Similarly, Publika journalists Aleksandre Keshelashvili and Basti Mgaloblishvili were beaten by police while filming the arrest of protestors on Rustaveli Avenue.

After the first violent clash in the evening of 7 March, protesters began to prepare with masks and helmets, demonstrating readiness to counter the use of violence. Videos of teenagers raving to a “siren disco” rather than dispersing and waving flags while facing the full strength of water cannons went viral on social media. This willingness to confront the violence exercised by the police took authorities by surprise and changed the dynamic of the protests.

“Gen-Z, these school kids, 16 years old, were so important, especially when it came to clashes and violence,” Florian Mühlfried, a professor at Ilia State University, observed. He emphasised that a proper analysis of the events must take the role of violence into account. “Though violence was not a dominant part of the protests, there were certain young people who were willing to confront violence with violence,” Mühlfried explained. “There was widespread uneasiness when protest organisers saw young people throwing stones, and at first they tried to persuade people not to do that. There was a learning process, with violence becoming accepted as a facet of the protest.”

Attempts to discredit the protests and Georgia’s youth participation

The violent clashes also led to attempts to frame the protests as anarchic and illegitimate, including via social media posts by pro-government trolls and Facebook pages.

According to Ani Kistauri, a researcher with the Media Development Foundation, there were two types of activities. One tried to discredit the protestors and political opposition, accusing the protestors of vandalism and violence; the other spread pro-government messages, focusing on the law’s necessity and justifying the government’s forcible dispersal of protestors. Addressing Georgia’s youth in particular, various Facebook pages wrote that these young people were “drunk, smoked, did not take care of the territory around the Parliament, and were polluting.” These same pages also claimed that the young people protesting had not read the law. In contrast, images went viral on social media showing young Georgians cleaning up after the protests.

Following the conclusion of the protests, Georgian Dream members continued to defend the bill, and added their own claims to discredit protestors. Most notably, on 12 March, Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili told TV Imedi that he saw some young protestors dressed in satanic costumes, and that Georgian students were just being used by the political opposition. The confrontation and polarisation in Georgian politics, evident in the eruption of the protests, are here to stay.

Why Georgia’s youth and why now?

Despite their important role, the role of Gen-Z in the protests took some people by surprise. “There was this prejudice that [Gen-Z] were all about clubbing and consuming, and were disinterested with politics, not really caring about their future,” Mühlfried says. “Finally there was visibility, they played a super important role. It was very different from what we thought, and it showed a section of society being recognised as citizens, who weren’t previously.”

For Chitiani, there were several possible reasons why Georgia’s youth emerged in force. For one, Georgia’s youth gain many opportunities from NGOs; naturally, there is a wish to protect their futures. Another aspect was the academic nature of some of the protest actions, such as boycotting lecturers. Finally, media use varies across generations. Today’s youth rarely watch TV, which is where a large amount of anti-protest propaganda is found. In comparison, the pro-protest narrative was widely spread across social media.

“There have been protests about many other topics, but none have had this kind of involvement from the youth — consequently, none have been as successful as this one,” Chitiani says. “This was the instance when young people (‘Gen-Z’) voiced their opinions in an unprecedented manner and ultimately got what they wanted.”

Though all generations were present in the protests, a notable achievement in itself, the zeal of millennials and Gen-Z struck a nerve with the public sphere. Amplified by social media channels, the actions of the protesters reached a wide domestic and international audience.

“There is this notion of learned helplessness and I think many of my generation and before me are subject to this. There are so many failures that we don’t see a reason to fight as we think we will fail. If you have not failed that much, you might be more eager to fight for things and more brave and actually get results,” Tsisana Khunadze, a psychologist and sociologist, said during a Facebook live discussion of recent events.

Though the draft law has been dropped for the time being, Georgia’s youth are still wary about the future.

“We believe that we still have a lot to do against Kremlin influence in the government. The government says that they will start an information campaign to explain the advantages of the law. In response, the [Students Against the Russian Law] movement is going to continue its campaign in order to spread information about future threats from Russia and their possible consequences,” Japaridze says.

Feature Image: Canva

Images: Mariam Mutidze

Xandie (Alexandra) Kuenning. Editor-in-Chief. MA student in Central and Eastern European, Russian and Eurasian Affairs. Interested in LGBTQ+ and gender rights, civil society, and culture, particularly within the Black Sea region.

Lukas Baake. Deputy Editor-in-Chief. After studies in Berlin, Paris, and London, currently based in Tbilisi. Interested in Russia, the EU´s external policies, the South Caucasus, and geoeconomics.