Big dams, big dreams: Rogun and Central Asia’s geo-economics of green energy13 min read

With Tajikistan reconnecting to the regional power grid, the EU, China, and Saudi Arabia are stepping in to fund the region’s hydropower plants, including Rogun, the world’s tallest dam.

The presidents of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan have been pursuing big plans. At COP29 in Baku, the three autocratic leaders sat down to seal a trilateral “strategic partnership” for a green energy corridor that envisages an undersea cable spanning from one side of the Caspian Sea to the other.

This project would not only draw Central Asia and the South Caucasus closer to each other; both regions hope to export solar and wind energy to European markets: first via a Caspian transmission line, then with an electricity cable along the bottom of the Black Sea, reaching from Georgia to Romania. The Black Sea submarine cable is already a project in the making, with Romania, Hungary, Azerbaijan, and Georgia in the lead, while the EU Commission supports the initiative as one of its “flagship” Global Gateway projects, promising financial support.

But when it comes to the Caspian Sea region, the EU isn’t the one basking in the limelight. Instead, during the signing ceremony of the “brotherly” Azerbaijani-Kazakh-Uzbek agreement, the three presidents praised Saudi Arabia and the Saudi company ACWA Power as their main partners.

Saudi Arabia makes headway into Eurasia’s renewable energy industry

Saudi Arabia looms large over Central Asia’s and Azerbaijan’s green energy partnership. Riyadh, in recent years, has signed several memoranda and agreements with the three countries. In Baku, the four governments established a joint executive programme in which the Gulf powerhouse will help to improve their energy efficiency, connect their national power grids, and build storage systems and wind farms. The hands-on work will be done by ACWA Power, alongside the Kingdom’s electricity grid operator, Saudi Electricity Co.

And small Tajikistan, too, is putting out some feelers to become a part of this green corridor. Talking to journalists on the sidelines of COP29, the Tajik energy minister brought his country into play by considering joining the strategic partnership – although he had to concede that his colleagues had not approached him with an official proposal yet.

All this points to larger developments that shape the multi-layered geo-economics of Central Asia — and beyond.

Central Asia lacks water — and electricity

Central Asia is one of the world regions most vulnerable to climate change. While its population is expected to grow from about 80 million to a figure somewhere between 90 and 110 million people by 2050, one-third of its inhabitants lack access to safe water.

Water resource management and energy supply have proven to be both unifying and dividing forces — especially when it comes to hydropower, which is generated from water flow and considered a highly climate-friendly — but not always environmentally-friendly — technology.

This is the dividing line separating Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan — with their vast mountain ranges and glaciers — from the rest of Central Asia, oil-rich nations with arid deserts and the great steppe. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan produce most of their electricity from the melting snow. But in the winter months they face power shortages and depend on energy supplies from their neighbours. Both countries have therefore set up mega-dams and water reservoirs for electricity generation, which, in turn, reduces the volumes of riverine water flows to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, causing conflict with Uzbek and Kazakh farmers whose lands dry up.

With that, the term “water diplomacy” has become key to the vocabulary of Central Asia’s international relations.

National egos, dinosaur infrastructure

History bears heavily on Central Asian politics. With Soviet central power gone, the region-wide distribution of electricity dissolved into a cacophony of national energy policies. Regional cooperation seemed old-fashioned, rather counterintuitive in the new age of national self-determination. Finally, in 2003, Turkmenistan became the first state to leave Central Asia’s unified power system, choosing to operate its grid in parallel to Iran’s.

Then, Tajikistan, in a rather humiliating move, was effectively expelled from the remaining group of four in 2009, after its neighbours accused Dushanbe of siphoning off electricity above its allocated share. According to other accounts, the Tajik expulsion came in response to a region-wide blackout, allegedly triggered by Tajikistan’s poorly maintained and outdated Soviet-era infrastructure. With the implosion of the regional power grid, both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan suffered severe electricity shortages during the winters to come.

Poor infrastructure remains a big problem. In a 2022 EU-sponsored report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that Tajikistan, so far, has exploited a mere 4% of its hydropower potential. Despite succeeding in providing universal access to electricity, Tajikistan is still vulnerable to water level fluctuations, leaving about a million people without reliable electricity supply in the cold months. The low quality of its transmission and distribution system has caused twice as many relative energy losses compared to the IAE average, according to the agency.

Back for good? Tajik hydropower for sale

Against this backdrop it is rather surprising that Tajikistan announced its decision to rejoin Central Asia’s unified power system.

Between 2018 and 2024, Tajikistan started exporting electricity in a so-called “restricted island mode.” In this arrangement, the receiving region in Uzbekistan was disconnected from the rest of the national power grid, to avoid new cross-border outages originating from Tajikistan. In June 2024, Tajik transmissions were finally extended to the western part of Uzbekistan’s national power grid.

Tajikistan’s return to the regional electricity network, however, has been driven by international sponsors. The Asian Development Bank (ADB), a financial institution in which the US and Japan hold majority shares, has played a leading role in updating the Tajik relay systems, saving the country’s bankrupt national energy company, Barqi Tojik, and pushing forward reforms in the energy sector.

In October 2024, ADB announced an additional grant worth $15 million to connect Tajikistan to Uzbekistan through another 22 kilometre transmission line that, in the long run, shall become a key component for exporting electricity produced by the Tajik Rogun Hydropower Plant (HPP).

Indeed, all eyes are on Rogun. It is, perhaps, the project that propels Central Asia’s shift towards stronger energy cooperation — and it makes the Tajik president’s heart skip a beat.

Set to be finished by 2037 and a project of national pride, the Rogun HPP will be the world’s highest dam, currently an awe-inspiring construction site on the Vakhsh river, just little more than a hundred kilometres from Dushanbe, the country’s capital. Not only would the plant’s annual capacity — over 3,600 megawatts — cover most of Tajikistan’s domestic consumption and help produce green aluminium (it is also rumoured to lead to a blooming cryptocurrency mining industry); the dam will also turn Tajikistan into a high-voltage powerhouse, potentially exporting about 70% of Rogun’s total electricity to regional neighbours and beyond.

No wonder Dushanbe sets an eye on possibly joining the Uzbek–Kazakh–Azerbaijani green energy corridor.

With profits in mind, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have softened their stance on Tajik hydropower

Nevertheless, the problems of Rogun circle back to the same old issues: it may reduce already dwindling water flows to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Uzbekistan was a particularly fervent opponent of the dam under its first president, Islam Karimov. His successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, however, has led the country to a gradual economic opening — and to rapprochement with Tajikistan.

Suffering from electricity shortages — Uzbekistan even struck a deal to import gas from Russia to generate electricity — Tashkent now sees the expected energy boom in Tajikistan as a chance to cover its own needs. The Uzbek government gave up its staunch opposition, and even committed to buying electricity produced by Rogun. Moreover, both countries plan to join forces to build two more small HPPs in Tajikistan.

Kazakhstan, too, is in talks with Tajikistan to import electricity from Rogun via Uzbekistan, addressing its growing energy deficits.

With regional opposition to the dam gone, criticism is left to civil society organisations that chide international banks for sponsoring a project that, allegedly, does not uphold its green promises. Whilst the EU, World Bank, and ADB praise Rogun’s contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions throughout Central Asia, regional watchdogs lambast the project’s ecological and social impact, pushing for a renewed impact study and demanding from the banks to call off support immediately. Furthermore, a coalition of NGOs has questioned the very claim that the HPP accelerated decarbonisation — instead, they reckon, Rogun would leave a bigger carbon footprint than generally assumed.

Long story short: A Soviet baby, given birth to in the 21st century, built by Europeans

With its decade-long history, Rogun has become an indicator of the economic influence of foreign states. Originally conceived by Soviet engineers, and with the first construction works having started in the 1970s, the project suffered several setbacks, including a civil war in the 1990s. Russia’s aluminium company Rusal failed to revive the project in the 2000s. Only in 2016 did bulldozers and excavators move in again — but with no one less than an unfazed President Rahmon sitting behind the steering wheel.

The first turbine was inaugurated by Rahmon in a big show two years later — broadcasted on public television on the Day of the President, a national holiday.

According to the Tajik government, the project employs about 17,000 labourers and technicians. The third turbine is expected to be put into operation in late 2026, while overall completion is slated for 2035.

In the lead of Rogun’s construction are chiefly European companies, foremost Milan-based WeBuild, formerly known as Salini Impregilo. The company prides itself with this project, as the HPP will provide as much energy as three nuclear power plants.

Italy, therefore, is one of Rahmon’s most important destinations when travelling to Europe. During his last visit, President Rahmon reportedly asked Italy for another $150 million in credit to complete Rogun.

But it is also a lucrative undertaking for Germany’s Siemens, which supplies two gas-insulated switchgears, as well as for Ukraine’s state-run Turboatom and Electrotyazhmash, which are responsible for the design and supply of turbines and generators.

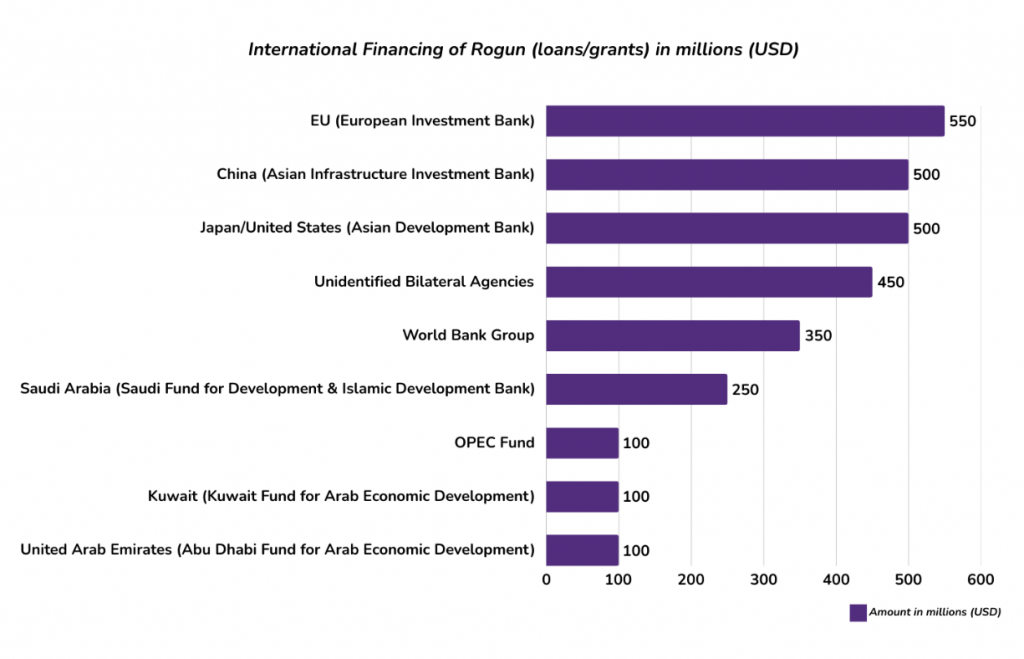

As with most prestige projects, the costs for Rogun have spiraled with the years. The government owns the shareholding and pays the lion’s share of the staggering $6.4 billion investment. But almost half of the costs are financed by international institutions handing out loans and grants to the Tajik state (which, of course, need to be paid back as soon as the cascade makes money rain).

European Commission: A new “Great Game” to contain China

As political influence travels along financial flows, it is worth taking a look at which countries and affiliated institutions are behind these loans. The results may surprise some observers.

According to the latest World Bank report, it is indeed the EU’s European Investment Bank (EIB) that has committed the largest foreign share with $550 million. For the EU, the construction of the Rogun dam has become another regional flagship project under its Global Gateway Initiative. Brussels, too, wants to double Tajikistan’s energy production and advance the decarbonisation of Central Asia. This isn’t just a philanthropic exercise but a hard investment in the region’s stability and conflict prevention, furthering the EU’s reputation as an honest broker and global partner. Yet, as an anonymous EIB official told Reuters, it is also a deliberate geopolitical move against Russia, intended to dent Moscow’s energy clout in the region.

In 2022, following Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the EIB was reportedly asked by the European Commission to get involved in the Rogun dam project – and to become no less than its biggest investor.

EU officials usually do not paint their projects as directed against anyone; instead, they stress the positive character and benefits of mutual cooperation. Nevertheless, an internal briefing document of the Commission’s Department-General for International Partnerships (DG INTPA), leaked by Politico in 2024, reveals a surprisingly frank, zero-sum mindset in Brussels, not only towards Russia, but also China.

“While the countries making up Central Asia have historically been in Russia’s sphere of influence,” reads the Commission document, “the current geopolitical context […] has opened a new Great Game.”

According to the internal paper, China was trying to replace Russia, and the newly appointed Commission “should not miss the opportunity to strengthen the EU’s position in the region [and] contain Chinese expansion.”

Similarly, after visiting Central Asia in 2022, the EU’s then-High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, used the occasion to stress that “[o]ur Tajik partners have chosen the high-quality EU offer over the low-cost Chinese one”, praising the EU’s 15% share in financing Rogun at that time. More recently, Brussels announced a contribution of €16 million to Sebzor, another Tajik hydropower plant.

Nevertheless, both the EU’s Commission and EIB have kept a rather low profile publicly. Little to no information on their commitment to Rogun can be found on the EU’s official websites.

But as interesting as the EU being tight-lipped is, the fact is that China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has likewise stepped up its financial support. With an investment volume of $500 million, Beijing is just a little less invested than Brussels — making Rogun a curious case where China’s renewed focus on a “Green” Belt and Road Initiative and the EU’s Global Gateway somehow converge.

Also worth noting is the fact that Middle Eastern actors, above all Saudi Arabia, have involved themselves with a similarly strong share of a combined $550 million. It shows that the Gulf monarchies – often omitted in geopolitical equations of Central Asia – should be reckoned with.

An investment into the future or a misplaced bet?

As the giant hydropower plant in Rogun is expected to be fully operational only in a decade from now, however, the activists campaigning against the dam may have a point: Will the plant remain as profitable as expected?

Technological changes advance rapidly, and China seems to have placed its bet on wind and solar energy, mainly in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. These two countries, in turn, have also shown a political turnaround on nuclear energy, planning to build a new generation of nuclear power plants, possibly changing the region’s energy market again.

Many other hydropower plants compete for international funding, too. Kyrgyzstan hopes to ride on the wave Tajikistan has made with Rogun, and President Japarov has proposed to Brussels making Kambarata-1 HPP a Global Gateway project as well (either way, construction works are scheduled to begin later this year).

Like Rogun, Kambarata-1 attracts a variety of multilateral business angels: World Bank, ADB, AIIB, Islamic Development Bank, OPEC Fund, and EBRD established a donor committee last summer; EIB joined shortly afterwards. And the Eurasian Development Bank — which is dominated by Russia — expressed interest in providing not less than $500 million for the dam’s construction. Official commitments, though, are yet to be seen.

So, there clearly is no lack of interest in Central Asia’s renewables. And the funds are coming in. Yet it is also a matter of geopolitical will for who pays what and why. In the end, a patchwork of multiple projects and potential energy sources emerges on the rugged terrain.

But is there a devised strategy that weaves them together in a coherent manner, serving all Central Asians? Perhaps, it will depend on the five governments to ensure that they don’t evolve into a plethora of unaligned ad-hoc initiatives with unintended consequences for each other.