Soviet Mosaics in Central Asia: The stories of Tashkent and Almaty7 min read

Once, the streets of the Soviet Central Asian capitals echoed with the footsteps of factory workers, students, and everyday citizens, moving past mosaics that showed the tales of space exploration, musical heritage, rich traditions, and local industries. These skilfully crafted mosaics transformed the urban environment with colourful imagery and cultural stories.

The Soviet Union saw public monumental mosaics as the perfect combination of artistry and a way of conveying ideas. On the one hand, they added beauty to otherwise very uniform and grey buildings, and on the other, the materials used are very resistant to all kinds of weather.

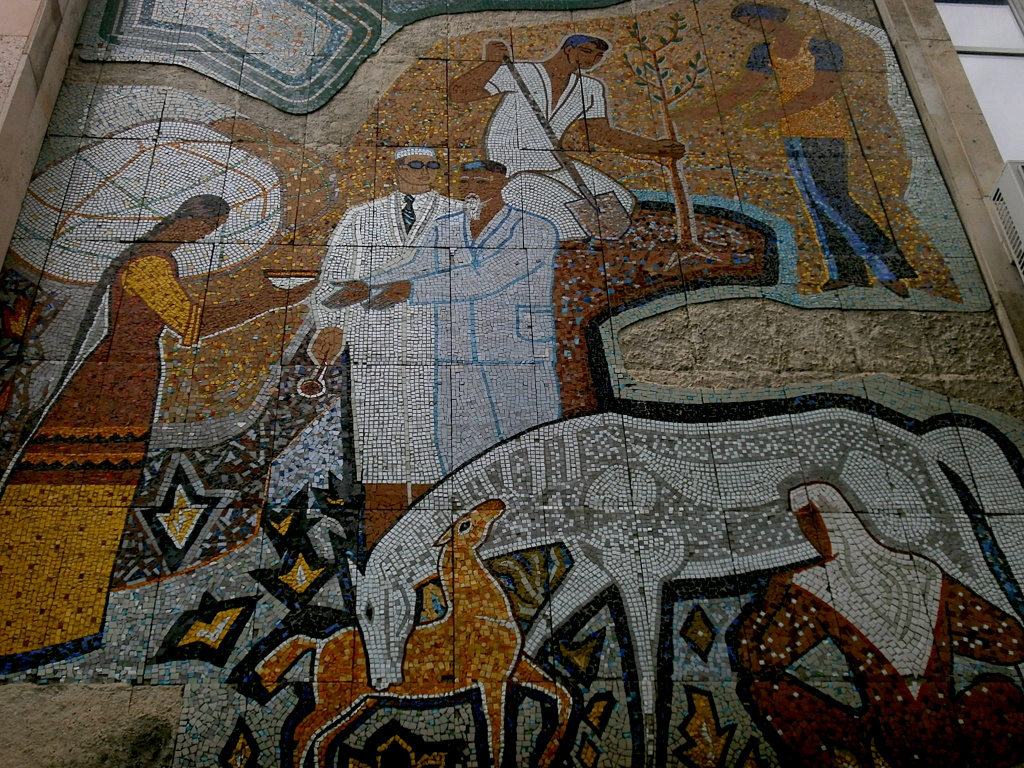

However, contrary to what one might assume, the mosaics in the Soviet Central Asian capitals aren’t huge portraits of Soviet political figures or exclusively the ideal, strong worker. Instead, the distance from the political centre, Moscow, meant that the state wasn’t paying so much attention, which allowed a certain freedom to local artists. As a result, they could mix Soviet elements and styles with local folklore and culture, creating a unique strand of Socialist Realism mixed with Islamic and national aesthetic and cultural elements and imagery.

Today, the Soviet Union having collapsed decades ago, many of these mosaics have fallen into disrepair. Modernity presses forward, but those colourful narratives are slowly vanishing, reminders of a time when 5% of public construction costs were devoted to integrating art into daily existence.

Protecting mosaics as artistic heritage: A new chapter in Tashkent

Over the last 30 years, many mosaics in Tashkent and Almaty have been painted over, demolished, or obscured by advertisements. However, a significant step towards preservation was taken on 25 March 2024, when the Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan issued a decree that designated 157 mosaics across the country as cultural heritage sites. This significant decision aims to protect and ensure that the stories these Soviet mosaics tell remain part of the urban fabric and enhance the country’s appeal to tourists.

It is not difficult to spot Soviet mosaics when walking around the Uzbek capital. Both the Soviet and posterior governments have seen the value in decorating façades with them, so similar that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the old and the new. Traditional patterns were first introduced around the city when it was rebuilt with huge apartment blocks after a devastating 1966 earthquake destroyed most of the city. The speed at which these buildings were completed left little time for architectural flourishes.

However, mosaics could fill this need for public art, explains the city council’s website, Mosaic Taskhent: “They wanted to give people something more than just new buildings. Each mosaic told its own story, gave emotions, diluted the grey landscape of high-rise buildings, marking the beginning of a new life and a new era.”

By protecting and restoring the Soviet mosaics in the city, the Uzbek government is not only acknowledging their artistic relevance, but also their uplifting role after the devastating episode. The website also aims to celebrate the heritage of the builders and artists behind the mosaics, many of whom were Ukrainian, researching and documenting their labour.

In 2023, the Uzbekistan Arts and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) launched the research and preservation project Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI, which explores the city’s modernist architecture. They organised the exhibition ‘Tashkent Modernism’, which explored the city’s modernist architecture while offering insights into the colonial, postcolonial, and decolonial aspects of the Soviet social and cultural experiment. They continue their documentation efforts through public submissions on their Instagram and app.

Almaty’s struggle with preservation

The former Kazakh capital shows a different reality. Without any kind of policy for the protection and preservation of public monumental art in Almaty, it is left to the building owners’ will, public or private. Mosaics are not included in the ‘List of protected sites of heritage of national value of the Ministry of Culture’, and very rarely are there any consequences for tearing them down during renovations. Even though, like in Tashkent, mosaics in Almaty depict national culture and imagery intertwined with Soviet styles and ideas, the government has yet to recognise and defend their value.

Instead, grassroots initiatives have had to take the lead in convincing the city council to stop its own plans, or to stop building owners from destroying any more national artistic heritage. Moreover, the government is responsible for the preservation of buildings included in the list of heritage sites. However, it seems from several cases in the past that this list is easily modifiable in favour of private interests, as Dennis Keen, local American and founder of the project Monumental Almaty, has observed over the years.

Keen’s project, with the help and collaboration of many locals, is attempting to document mosaics, artists, and their methodologies, as well as make a change from the bottom up. “We’ve seen some instances of the local government reaction to public outrage about certain projects by adapting their previously announced plans,” Keen told Lossi 36, although in other cases mosaics have been destroyed by the city council while ignoring public concerns. However, it seems that the public’s appreciation for the art hasn’t gone unnoticed: very recently, a mosaic was found during the restoration of a bus station and instead of being destroyed, it was transferred to the hall of a visitor centre. This is not the first time a mosaic has been moved somewhere else to preserve it, leaving the original building able to be renovated.

The mosaics in Tashkent and in Almaty have a nationalistic, nostalgic feeling for the local traditions before the Soviet Union, which was a common theme across the region for all artists to explore. Folklore stories of love and bravery, national clothing, and traditions, including food and instruments played by local men and women, are clear in the installations.

Although this might seem contrary to the propagandistic and uniformising efforts of the USSR and its promotion of Socialist Realism, the central government highly valued public art as a form of inspiration and education, and realised that by allowing national elements into the cities of Central Asia, their inhabitants might better connect to the art, and appreciate the messages it encapsulated. This did not mean any or all imagery, though.

Especially for the decoration of buildings in Tashkent, the artists specifically chose almost abstract shapes and patterns that could be separated from their religious or historical origin, and which did not depict anything specific. Despite the style originating in Persian and Islamic traditions, which arrived in Central Asia through the Silk Route, the USSR wanted to remove any ideological influence from the decorative expression.

Of course, one cannot avoid the portraits of astronauts, the idealised, strong Soviet workers, or the celebration of scientific and sports achievements. Socialist Realism might have been mixed and intertwined with local ideals and national aspirations in Central Asia, but that did not mean the Soviet Union did not care at all about what was being placed on façades, especially on government and administrative buildings.

In Almaty and in Tashkent, the mosaic artists were both local and international. The depictions of national elements and folklore, local people, and sometimes images and scenes completely disconnected from the Soviet Union’s more prominent and imposed socialist realism style show that, beyond seeing public art as propaganda, the creators of these installations had a genuine intention of embellishing the cities and sharing with their people.

The preservation and restoration of Tashkent’s mosaics not only safeguard a vital part of its cultural history but also honour the artists who, despite an era of artistic repression, found ways to adorn the city. This history highlights that art, even when created under political control, remains a powerful tool to maintain beauty, inspiration, and a sense of identity. By embracing and protecting these vibrant mosaics, Tashkent offers a hopeful example for other cities, demonstrating that cultural heritage can be a lasting source of pride and a testament of a collective identity in an ever-changing world.