Identity and revolution. The new musical scene in Ukraine16 min read

In December last year at New York’s Carnegie Hall, the Ukrainian National Choir performed “Shchedryk”, a work better known as Carol of the Bells, the world-famous Christmas melody that few know is of Ukrainian origin.

Its composer was in fact Mykola Dmytrovych Leontovych and the concert organised in New York sought to replicate the first overseas performance that took place in 1922 and which, a few years later, would lead the song to international fame.

At the same time, this centenary presented an opportunity for Ukrainians to claim the national origin of the song, thus reaffirming their cultural richness and identity, an issue that is more sensitive for them than ever. It is no coincidence that this melody inspired a Polish-Ukrainian movie entitled Shchedryk, in which the song acts as a soundtrack and a fil rouge linking the tragic story of three families (Jewish, Polish, and Ukrainian) forced to go through first the Nazi regime and then the Soviet period. In this film, the process of exalting the identity of the song is evident to the point of verging on the pathetic. But the concert at Carnegie Hall and the video message that the Ukrainian first lady gave to recount the origin of the song, make it clear how the message of identity is also conveyed in Ukraine through music.

In these hundred years, many things have changed, but others still seem to be the same, only represented in other forms and under other names: among the things that have remained unchanged is surely the deep link between the Ukrainian identity and music.

Neofolk

It is no coincidence that the two-tone yellow-and-blue has appeared on the Eurovision podium more than once in the last 20 years. Last year’s competition saw Kalush Orchestra triumph with “Stefania,” after Go-A took second place in 2021 with the viral hit “Shum.” Before that, the trophy in the form of a crystal microphone had been taken home by singer Ruslana in 2004 with “Wild Dances” and in 2016 by Jamala with the song “1944.”

Listening to these four songs, it is possible to detect a lowest common denominator that somewhat suggests the new course taken by modern Ukrainian music: folklore.

The incursion of folklore into music is certainly not a contemporary phenomenon; it has been present since the dawn of time (or, rather, since the birth of the notion of folklore). In the more modern Ukrainian musical tradition, hints can already be found in the work of Ukrainian jazz musician Igor Khoma, who was inspired by folk motifs for his compositions (an example is “Arkan”, a piano composition whose music is inspired by the Hutsula tradition).

Again, in the 1990s, the Lviv-based group Mertvyj Piven combined folk elements with a rock sound, making the group one of the first truly successful rock experiments in an independent Ukraine (together with Braty Hadjukin, another eclectic and legendary group). Some of their songs are transpositions into music of verses from Ukrainian poems, such as those by Serhiy Zhadan, Yuri Andrukhovych, or Taras Shevchenko himself. One example is the album Zapovit, which refers to the famous poem “Testament” of the Ukrainian national poet.

But in the context of modern Ukrainian music, artists have elevated the folkloric element to a true trait of their national identity . This aspect presents itself in various forms: in the choice of using popular musical instruments, in the singing style, in the re-adaptation of folk melodies, up to the use of stage costumes and traditional symbols.

Ruslana’s piece, for example, opens with the sound of the trembìta, a long wooden horn mainly used by the ethnic groups present in the Carpathians (particularly the Hutsula) but also widely used in Romania. The film Tini nezabutykh predkiv (en.: The shadows of forgotten ancestors) by the Soviet-Armenian director Sergei Parajanov, set in the Carpathian mountains, is permeated by the sound of this instrument.

Jamala, recalling the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, uses the duduk, which is called ‘the Armenian oboe’ and was proclaimed an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in 2008.

The songs of the Kalush Orchestra and Go-A (groups which, by the way, share the participation of flautist Ihor Didenčuk), are characterised by a fusion style, in which folkloric motifs are accompanied with the use of electronics and rap music, as well as a careful choice of symbols and costumes. While Kalush extensively incorporates wind instruments such as the sopilka (Ukrainian wooden flute), Go-A instead focuses more on the elaboration of lyrics and melodies, taking up and re-adapting Ukrainian folk songs in a contemporary manner. This is the case with the song “Shum,” of which the main motif is taken from the Vesnjanki, Ukrainian folk songs dedicated to the arrival of spring (vesnà means spring in Ukrainian), still sung, taught, and loved throughout the country.

The enormous heritage of Ukrainian folk songs has led to a true cultural revival with the aim of preserving this heritage. As proof of this, 2018 saw the birth of the Polyphony Project, which consists of the virtual mapping of folk songs found in the country and recorded directly from the babusi, the Ukrainian grannies living in the villages. The naturalness with which these songs are performed hardly leaves one indifferent and further enhances the work of the project, which is a true electronic archive of an ‘intangible’ asset. For those who are keen on singing, the site is also interactive: it is possible to sing along to the recordings, following the words of the text transliterated in the Latin alphabet and silencing one or more voices in order to follow a single melody.

But the first real experimentation with folktronica is to be found in Katja Chilly: her album ”Rusalka in da House” is a real slap in the face of the taste of the time, a daring experiment on the borderline between innovation and tradition, enriched by the sound of the late 1990s.

From this experience developed the tendency to fuse folk and electronic music that now characterises the Ukrainian art scene and that had a strong influence especially on Nata Zhyzhchenko, stage name of ONUKA, a true phenomenon of Ukrainian neofolk.

Grandson of Oleksandr Šl’ončyk, the famous master of folk instruments, ONUKA is actually a project involving young Ukrainian musicians including Daryna Sert, Marija Sorokina, and Yevhen Yovenko. The latter, in particular, is a bandurist by profession (the bandura is a Ukrainian folk instrument with a sound similar to that of the lute, which is now also making a comeback in contemporary music). ONUKA’s songs make extensive use of these popular instruments: the album Vidlik is a prime example, and the song of the same name sees brilliant use of the buhaj. The buhaj is a wooden cylinder closed on one side with animal skin, in the middle of which a long, thin horse tail is then inserted which, when pulled, generates a deep bass sound: this is what can be heard in Vidlik, built entirely around the bass line. Buhaj in Ukrainian actually means bull, and the name derives from the deep sound of the instrument that recalls the cry of this animal.

We also find musical experimentation in ONUKA’s latest album, which features the collaboration of DakhaBrakha, another founding pillar of Ukrainian neofolk.

DakhaBrakha is a project born in 2004 based on an idea of Vladyslav Troitskyi, director of Dakh, a contemporary art centre in Kyїv founded in 1993. The name, in addition to being a tribute to the artistic reality of the capital, also refers to the ancient Ukrainian saying daty/braty (en.: to give and receive). Within a few years, the group managed to achieve incredible success within the country, becoming a true milestone of the new musical renaissance. Their uniqueness lies in their musical heterogeneity (all members are multi-instrumentalists), their singing technique ranging from pop to folk, so much so that they have defined their genre as ethno-chaos. Their songs are mainly inspired by Ukrainian, Russian, and Tatar-Crimean folk motifs (for example, “Salgir Boyu” is sung in the Tatar language). The project also takes on theatrical overtones at times, starting with the choice of costumes: unmistakable are the long, shaggy black hats worn by the singers.

A cornerstone of the project is the Dakh Daughters collective, consisting of seven multi-instrumental musicians: the project was founded in 2012 and has always orbited around the Dakh art centre. Their repertoire alternates between acting and singing and is based on texts in various languages (mainly Ukrainian, English, French, Russian, and German). Their performance in December 2013 during the Euromaidan protests became famous: in the video it is interesting to observe their stage preparation, during which the artists put on make-up and dress, a ritual that has also become an integral part of their performances and which take place directly on stage, in front of the spectators.

ONUKA, DakhaBrakha, and the Dakh Daughters are of course just some of the most representative names of the neofolk projects that have sprung up in recent years. Other unavoidable artists to cover this scene are Alina Pash, a candidate to represent Ukraine at Eurovision 2022, the trio KAZKA (famous for their single “Plakala o Cry,” whose video clip set the record for the most viewed Ukrainian-language video ever), the duo Yuko, and the less famous (for now) Zitkani.

Between doom and indie

The doom scene is also particularly rich and in vogue, although unfortunately it still remains little known and appreciated internationally. Some of its representatives can be found in Palindrom, whose rap tendency could rather be described as nu-doom; and also in Mistmorn and SadSvit, two solo projects whose songs are characterised by decidedly more post-punk and lo-fi sounds. Definitely reigning in this wake are Kurs Valüt, an EBM ensemble from Dnipro who formed in 2017. The lyrics of their songs feature Ukrainian memes and philosophical poetry in industrial sounds: the song “Veselo,” for example, is based on the words of the poet Pavlo Tychyna, and “Kurs Valüt,” on the other hand, offers parts of the poem “Vsjakomu mistu – zvyčaj i prava” by Hryhorii Skovoroda, the Ukrainian philosopher par excellence who is also depicted on the 500 hrv note, with a profoundly Platonic thought.

Other examples worth mentioning are Ferba Kingdom and Džosers (Джосерс), the latter straddling the line between post-punk and indie.

The Ukrainian indie scene is definitely dominated by Odyn v Kanoe (en.: Alone in a Canoe), an ensemble from Lviv formed by singer Iryna Shvaidak, guitarist Ustym Pokhmursky, and percussionist Ihor Dzikovsky. The song “Choven” (en.: the Boat) has become a real catchphrase among young Ukrainians, especially since it is the transposition to music of the poem of the same name by Ukrainian national poet Ivan Franko.

In the wake of Odyn v Kanoe, it is worth mentioning Khrystyna Solovyj: the singer, who became famous in 2013 for her participation in Holos Kraїni (literally The Voice of the Country, the Ukrainian equivalent of The Voice), achieved international success with her music video for the song “Trymaj”. The song is part of the album “Zhyva Voda” (en.: living water), which takes up popular motifs of the Lemchi, a Slavic ethnic group also known as Ruthenians and present mainly in the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine, but also widespread in various parts of Poland and Slovakia. The decision to dedicate an album to this ethnic group was prompted by the singer’s discovery that she is one-quarter lemka.

Kyiv as the new Berlin: Ravevival

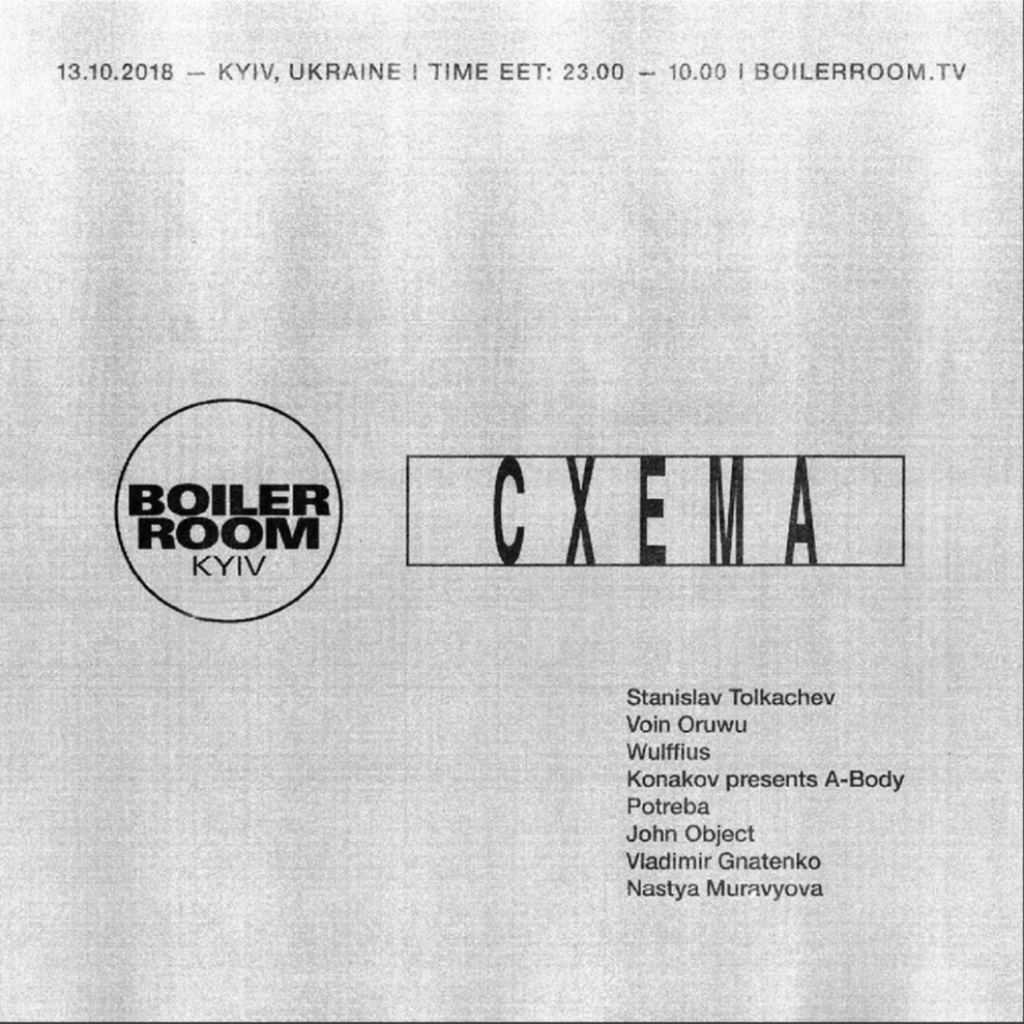

When recalling the events of 2013-2014, Ukrainians hardly use the expressions Euromaidan, Maidan, or Revolution of Dignity, as is common in Western media and publications. For Ukrainians, Maidan was simply the Revolution. This is because the country has experienced three revolutions in thirty years, but the last one represented a real turning point that dictated a new course for Ukrainian political, economic, and cultural history. It is no coincidence that one of the causes that also allowed the development of an indigenous techno scene was precisely this revolution. On the one hand, there was the general feeling of bewilderment and insecurity felt by many young people at the time, combined with the fear of an impending large-scale war, which in return generated an unconscious escapist desire. On the other hand, the refusal of many international artists to go to Ukraine to perform, frightened by the political instability of the country, contributed to a vacuum which soon had to be filled. The antidote for this predicament would be СХema.

CXema is a project developed by Slava Lepšeev who, like many in Ukraine, found himself out of work after the Maidan revolution. The idea of the project was to illegally organise various rave parties in abandoned places in the capital, and so, in a few months, through word of mouth and the distribution of flyers, the phenomenon conquered the whole of Kyїv, subsequently spreading like wildfire to the rest of the country (Lviv, Dnipro, Kharkiv, Ivano-Frankivsk).

CXema literally means scheme, but in a further sense, it is used to indicate a risky situation, precisely because at the beginning, the organisation of raves entailed precisely this: the risk of the police arriving to sabotage the evening, the gamble of being discovered.

The phenomenon went viral and grew to such an extent that it attracted the attention of various international media, as evidenced by the reports on the Ukrainian subculture by i-D, which contributed to making the phenomenon known also in the West, earning the Ukrainian capital the nickname “new Berlin.”

And it was precisely on the CXema stages that some of the most renowned Ukrainian DJs began their careers. Among these is Dmitrij Avksentiev, who is better known in the country as Koloah or Voin Oruwu and over the years has obtained various collaborations with international labels. There is also Nastya Muravyova, a potential Ukrainian Stella Bossi: very young, originally from Kyїv but currently residing in Prague, she has performed at festivals such as Unsound in Krakow, Pohoda in Slovakia, as well as being a regular in Berlin. She also actively collaborates with VESELKA, another new Ukrainian reality born in the context of CXema, which organises queer parties and LGBTQ+ friendly evenings. The name of the project refers to the Ukrainian word for rainbow, as the aim is to create events where everyone can feel free to express themselves without being discriminated against. The project, born in 2018, is once again linked to the city of Kyїv and is the result of the initiative of S. A. Tweeman, stage name of DJ Stanislav Tviman.

At the same time as the emergence of a new audience, Ukraine has also seen the appearance of many alternative hubs ready to accommodate the new demands of young people. These include the iconic club Closer, located in the Podil district of Kyïv, the historical heart of the city and the centre of Ukrainian nightlife, along with the more recent ∄, the club ‘that doesn’t exist’: opened in 2019, ∄ is also known as K41 (from the initials of the address and the house number where it is located, vul. Kyrylivs’ka 41) and is housed in a building inspired by the Berghain club in Berlin. The club follows the rigid and oxymoronic policy of anonymity and non-existence: in fact, the name refers to the symbol used in mathematical calculations to indicate the value of a formula that does not exist, like this club. All information about its events circulate exclusively on various Telegram channels or on their website where, after the beginning of the war in Eastern Ukraine, they launched a community fund to collect donations and help internally displaced persons. In the fund you can also find their playlist linked to the club’s associated label, Standard Deviation.

The rave phenomenon in Ukraine is not exclusive to the revolution, but it certainly constituted its rebirth. Even in pre-Maidan Ukraine it was possible to find similar examples, notably from 1993 to 2003 in the Konzatyp Republic, one of the first and biggest electronic music festivals in the post-Soviet space that took place on the promontory of the same name in Crimea, on the Sea of Azov, and that formed a whole generation of people who would organise festivals a few years later. From 2014 onwards, Ukraine struggled to keep up with all the festivals, such as Strichka (en.: ribbon), Brave! Factory Fest, and NextSound, to name just the most famous ones. For those seeking more variety, there is the GogolFest and the Leopolis Jazz Fest.

Music in times of war

In the aftermath of the large-scale Russian invasion, many artists (not only those related to the world of music) explicitly said they would not participate in events where Russians not opposing the war were expected to be present, inviting the organisers to cancel the concerts. In October 2022, a decision was officially taken by the Ukrainian Parliament: since then it is no longer possible to listen to Russian music on means of transport, in public places, and through public media sources. The ban affects those Russian artists who have not publicly denounced the aggression against Ukraine and who, in this case, ended up on the “black list.” On the other hand, the law provides for an increase in the circulation of music in the Ukrainian language: this means that Ukrainian Russian-speaking singers will still be able to sing in Russian, but the radio schedules must cover at least 75% Ukrainian-language productions.

However, already since 2014 the number of Ukrainian speakers has increased significantly and the 24 February invasion has only accelerated this process, with around 40% of Russian-speaking Ukrainians deciding to adopt Ukrainian as their first language. All the songs released from 24 February onwards are strictly in Ukrainian, such as the one launched by musician and producer TУЧА (Tuča, i.e. Marija Tučka), who transposed into music what has now become the Ukrainian slogan of this war – “russia is a terrorist state” (russia spelled voluntarily with a lowercase letter) — or, most recently, on the anniversary of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, founded on 6 December 1991, the song launched by Zhadan i Sobaki, the ska group of the famous writer Serhij Žadan, who has been active on the music scene for 20 years now.

These two pieces are of course just a drop in the ocean of songs produced this year. For those curious about the rest, there is a constantly updated playlist created by Slukh, the leading Ukrainian music and culture media founded in 2018.

It is inevitable that as a result of this war, “after the victory” (pislja peremogy), as Ukrainians are fond to say, music will still evolve in the opposite direction of the Russian radius of influence, but without necessarily approaching that of the West. It is perhaps intriguing to think that it will rather tend to fold in on itself again, continuing to follow and build an autonomous and independent style, aspiring to celebrate the identity that they decide to build for themselves: a dynamic that can be imagined a bit like the movement of a dancer who, concentrated in the repetition of the exercise, does nothing but rotate on herself in a whirlwind of pirouettes until she reaches her criterion of perfection.

This article was originally published in Italian on 23 March 2023 by our media partner Estranei. It was translated into English by Lukas Baake.