Barbie in Transnistria: Entering the fantastic world of Mark Verlan8 min read

Not long ago, during an afternoon in the library, I discovered by chance a truly brilliant booklet. It was an illustrated guide to the places, customs, and habits of a small post-Soviet republic called Molvanîa: its creators had fun constructing a collage of Western stereotypes towards everything further east, with the same taste for the satirical and lunatic as Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat. Molvanîa is an absurd country, where similarly weird languages are spoken and the population is distinguished by many bizarre habits, the infrastructure functions poorly, and the bureaucracy is practically non-existent. As I leafed through the guidebook, I couldn’t help thinking that Mark Verlan would have lived very well in Molvanîa with his paintings, sculptures, installations, and who knows what other projects.

Verlan’s work, which in Europe is practically unknown even to those who deal with contemporary art, was not particularly appreciated in his native Moldova, along with the oddities that made him “a clown, craftsman, sculptor, poet, sentimental trickster or thug,” to quote the phrase used in the catalogue of one of his exhibitions. And in fact, Verlan (1963-2020) was a stalwart character, who lived through the last years of the Soviet Union full of socialist realism, circus shows, and triumphant astronauts, and immediately enjoyed poking fun at all that iconography in a completely free way. The lack of precise biographical information speaks volumes about his desire to remain an outsider to the art world and its system, for which he cared little. Only the names of the identities he liked to create remain: Marian, Mark, Marik, Marioca sin dodzhea (En: “Son of the rain”) and many others represent the nuances of his personality.

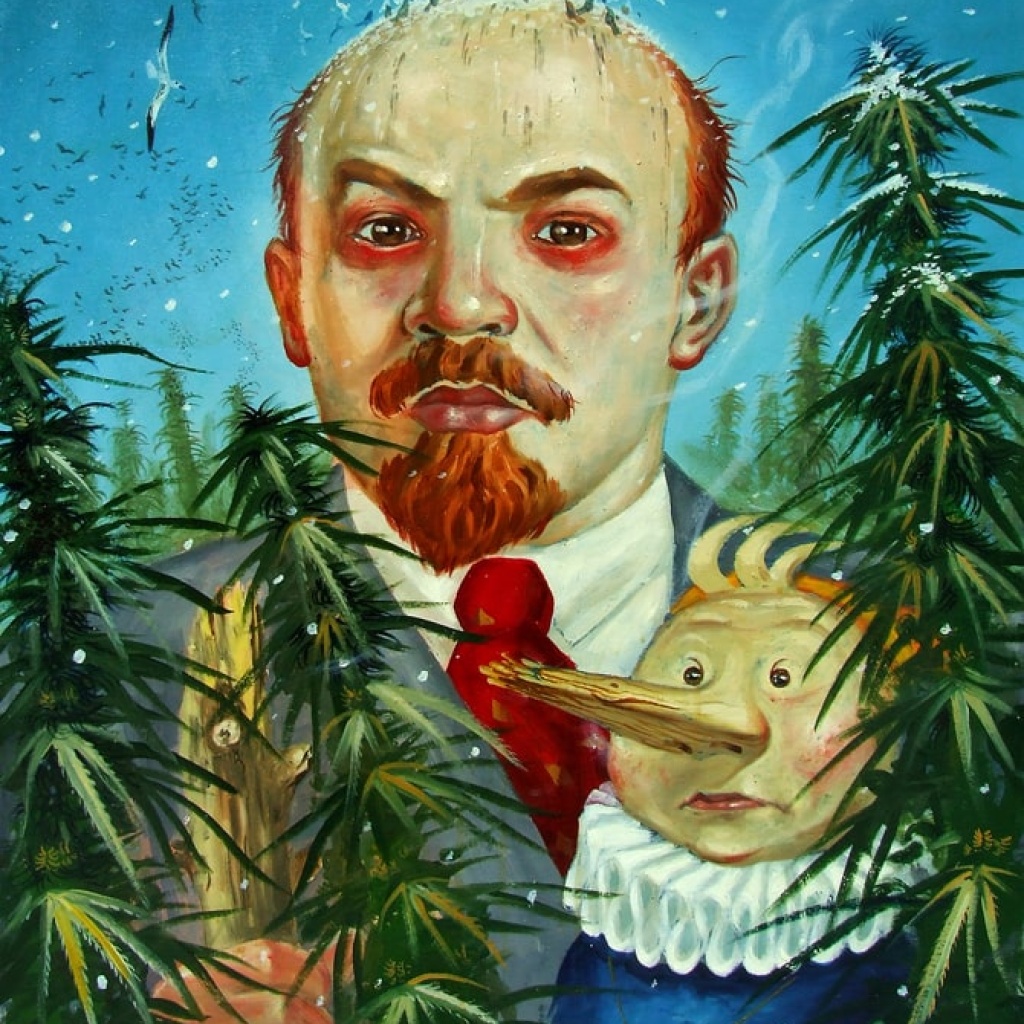

It was Verlan himself who, in one of his rare interviews, told how it all started when he was a young boy: while smoking with his sister under a big tree, “suddenly there was a loud clap of thunder, it started raining and something happened in my brain. I realised that I would never be a thresher, electrician, soldier or cosmonaut, but an artist. ‘Son of the rain’ is an allegory, because in a way I was born in the rain.” This was the beginning of an unconventional and creative activity in which Verlan, after studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Chişinău, tackled every artistic form of expression, ranging from painting and sculpture, assemblage, graphics, and visual poetry to photography and performance. All of these works never take themselves seriously as the direct result of Verlan’s absurd but triumphant ideas. This is as much the case for the funeral he celebrated with a large group of citizens in 1995 for a Barbie found without a leg in the street as for the display of military ushankas that look like excrements, along with portraits of Lenin with Christmas trees replaced by lush cannabis plants.

After all, the artist liked to play with all the symbols of power of both Soviet and contemporary Moldova: he even created a state entity called the Rainy Realm, equipped with a flag, an invented official language, and a customised currency as only the authors of Molvanîa could have thought of. There is also a map that Verlan had constructed for the Realm, a continent in the shape of Moldova amidst the other landmasses. The country moved every time Verlan moved, as his friend Octavian Eşanu recalls, precisely because artistic activity and personality were one and the same thing for him. In short, there was no separate studio or workshop; Verlan’s home was his kingdom and at the same time his forge of ideas for the works in motion. This absence of discernible borders must have always been present in the artist, who lived in the complex reality of Moldova all his life and learned to come to terms with it; all the more so because Cocieri, the village where he was born, is the only one in Transnistria to have rebelled against the separatists in 1991.

I became aware of Verlan’s work while working on my research thesis on an exhibition curated by Harald Szeemann, which brought together contemporary artists from twelve Balkan countries. That this group included Moldavian artists is not a random choice, considering that Szeemann travelled far and wide from Slovenia to Greece because he wanted to discover artists from this large region in the south-east of Europe; an area that has always been deemed too oriental for the Western gaze to be truly part of the European community, but not enough to be considered completely ‘Orient.’ It didn’t take long for Szeemann, who was so fond of the bizarre and the unexpected, to be thunderstruck by the artist’s work and personality. Deep down, I think he saw in Verlan the trickster he could not find anywhere else in art, the trickster with pockets full of ideas and an ace always up his sleeve, starting with their missed meeting. History has it that Szeemann flew from Switzerland to Chişinău to discuss the exhibition project with Verlan who, however, made himself untraceable and disappeared for the duration of his stay. The fact remains that Verlan earned himself a personal section within the exhibition Blood and Honey. Future is at Balkan (2003) at the Essl Foundation in Klosterneuburg, with twenty-five works including paintings, ceramics, and lithographs.

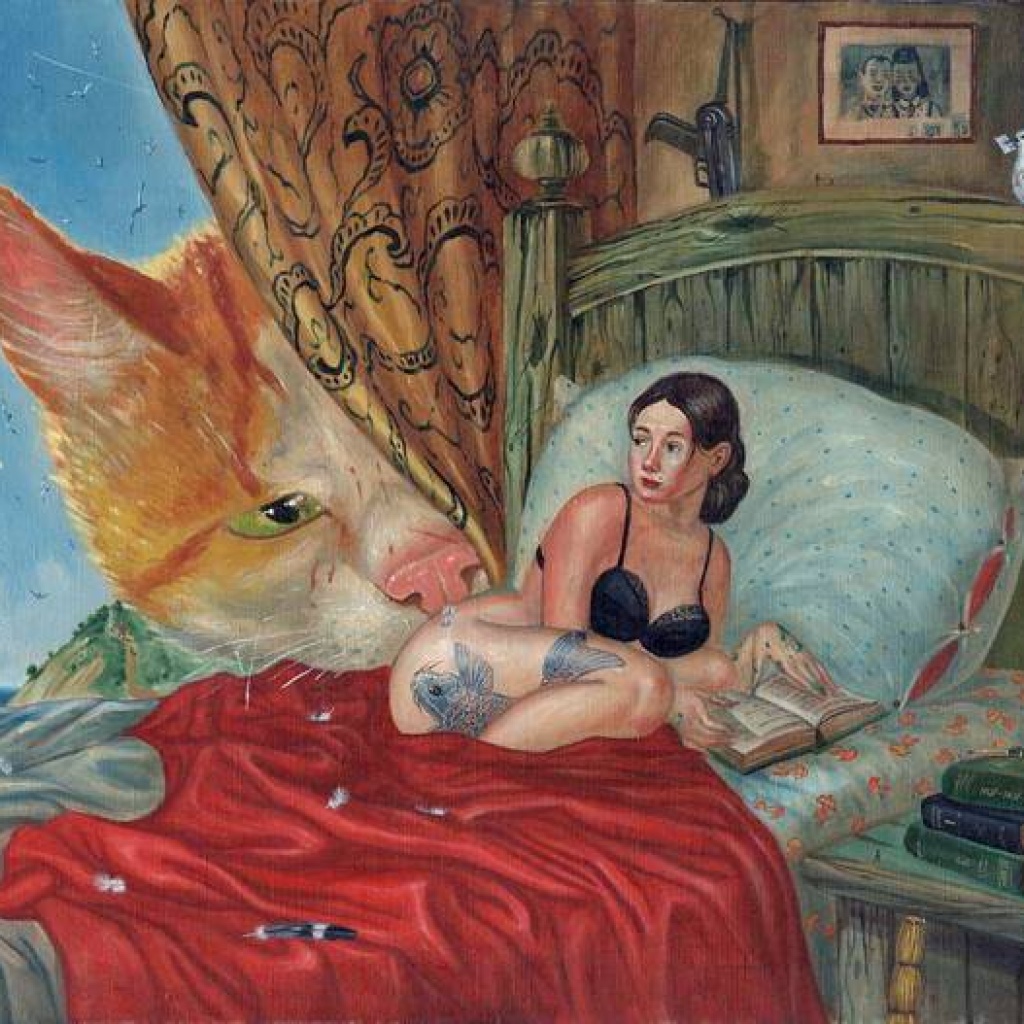

Particularly interesting are the two oil paintings chosen by Szeemann. Ostensibly, the viewer is confronted with an example of the socialist realism found in all museums and galleries in the Soviet Union, with huge statues and monuments towering over the bustling city. When looking at this type of work, the static nature of the stone monument stands out, solemn as only the party leader can be, in contrast to the speed of the metropolis, which, however, is complementary to it: large (monuments) for equally large capitals. Verlan works precisely on this relationship and suspends it, decides to render everything motionless for a moment in the city, which the footage of Ėjzenštejn and Dziga Vertov had always shown in motion. In his work Moscow (1994), we seem to be in a desert, or rather in the setting of something old and colossal, with the ruins of stone buildings and communist leaders being swallowed up by the sand and the fiery red sky. New York Under Water expands the discourse to America and shows us the Statue of Liberty in the middle of the ocean, not far from a woman sleeping blissfully in her underwater chamber. There is no trace of the maddened motorists, the whirlwind of people crossing the streets and the factories, just a view of something that is now hopelessly in ruins.

Verlan’s art returned to Western Europe in 2011, in the space dedicated to Transnistria, having its debut at the Venice Biennale. To be fair, the official press kit presented Transnistrian artists as representatives of Moldova, but the two countries had separate exhibitions, as one can imagine from the political situation. Verlan was exhibiting together with Aliona Kononova and Igor Avramenko in a collective named Art Group Moe: instead of a pavilion or a small gallery in some alley in Venice, the artists choose a squero, one of the shipyards on the water where gondolas are built, for the exhibition. The workers continued to work on the boats inside this very strange pavilion, which perhaps no one expected up to that point; on one wall was taped a sheet of paper indicating that this was the Transnistrian exhibition, while on the shore Verlan presented another artistic stunt. In fact, our freak took the door from his own house and placed it right behind the craftsmen and gondolas, with lots of shoes and knick-knacks hanging from the frames and on the threshold. A door without walls or foundations around it that comes straight from Eastern Europe: the artist cannot separate himself from what he creates and from his forge, not only mentally but also physically, and so he took it with him all the way to Italy to the city of the Biennale.

Every now and then, I wonder what Verlan would have come up with if he had not died of a heart attack almost two years ago; the Contemporary Art Centre of Chişinău has collected a lot of material on him since 1995, an archive that Verlan may have not care much about but which will be useful in reconstructing his life-long artistic endeavours, along with the great work that Octavian Eşanu carries out in order not to let him be forgotten. His funeral had little resonance outside his circle of friends and acquaintances. A ceremony at the cemetery was not attended by any official institution apart from the Contemporary Art Centre, which organised a memorial parade in a spirit similar to the one for Barbie twenty-six years earlier. As Eşanu recounts, the procession followed the coffin and the flag created by Verlan, “a black cat sitting in a sort of yin and yang, as if in a meditation position” on a green background. It was a fitting tribute to Verlan and his irony.

In any case, Mark Verlan did not stop pursuing the total work of art that was his life until the very end. Lilia Dragnev remembers that Verlan was developing impossible ideas, such as an exhibition in orbit and a lift to connect the two poles of the Earth, which he nevertheless tried to put together as if they were business as usual. There was also a series of letters he wrote to the most disparate people, including the Vietnamese government, Tina Turner, and the new President of Moldova, Maia Sandu. All stuff that seems meaningless, if you don’t take into account that “all of this was part of a large, absolutely complex and continuous artistic project called Mark Verlan.”

This article was originally published in Italian on 15 December 2023 by our media partner Estranei. It was translated into English by Lukas Baake.

Feature Image: Canva

Images: Estranei