“No one feels safe”: life in Nagorno-Karabakh after the war8 min read

Whilst the rest of Europe tries to fight the pandemic, residents in the remaining Armenian-controlled parts of Nagorno-Karabakh continue to suffer the effects of a devastating war.

“Karabakh is ours, Karabakh is Azerbaijan!” These were the words of Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s President, declaring victory in the second Nagorno-Karabakh war on 10 November 2020. Despite the proclamation of total victory, much of the region’s territory remains under Armenian control, including the capital Stepanakert, where life goes on.

The weather is getting warmer. People go to the market to buy food. Children go to schools which have long been reopened. Over 90,000 people on the Armenian side left Nagorno-Karabakh during the war and, whilst the majority have returned, many cannot go back to their homes as they are now under Azerbaijani control.

“Everywhere there are queues,” says Tatev Khachatryan, a journalist based in Stepanakert. “A great number of people lost their homes and the financial situation is unstable. Queues for food and services are usual for today’s Stepanakert.”

The long shadow of war

In November last year, the ceasefire agreed between Armenia and Azerbaijan brought an end to the fighting, six weeks after Azerbaijan launched a full-scale attack on the Armenian-controlled disputed region.

Six months on, the conflict is still acutely felt on the Armenian side. Between 140 and 240 Armenian prisoners of war have not yet been released by Azerbaijan, and human rights groups have brought to light evidence of their torture in captivity. Azerbaijan denies holding any prisoners other than on terrorism charges.

See also | On the frontline for 44 Days: the footballers in Nagorno-Karabakh who became soldiers overnight

Many families still do not know whether their loved ones are alive, with no information provided as to whether they died in the conflict or are being held in detention. On 8 April, a plane reportedly carrying 25 released prisoners turned out to be empty when it landed in Yerevan, despite crowds of hopeful relatives gathered at the airport.

In Nagorno-Karabakh itself, the effects of war cast a long shadow over everyday life. Reminders of last year’s devastating conflict can be found everywhere in the form of destroyed buildings and unexploded munitions.

Returning refugees arriving in Stepanakert by bus / Garik Avagyan

Returning refugees arriving in Stepanakert by bus / Garik Avagyan

Damage from the war at one of Stepanakert’s schools / Garik Avagyan

Damage from the war at one of Stepanakert’s schools / Garik Avagyan

A crater caused by shelling in the middle of a football stadium in Martuni / Armenian Geographic

A crater caused by shelling in the middle of a football stadium in Martuni / Armenian Geographic

Some also feel they cannot live peacefully in the capital, when the second largest town of Shushi (known in Azerbaijan as Shusha) is now under Azerbaijani control, just 10 kilometres away.

Once a multiethnic city in the Soviet era, Shushi is home to various Armenian churches, and reports of their desecration make people fearful for their cultural sites. Satellite images reveal that the Kanach Zham Church has been demolished since the war, part of what Armenians see as a ‘cultural genocide’ against them.

Civilians also worry about their personal security. Those in border areas have reported being intimidated with rocks and even rifle shots from the Azerbaijani side.

“No one feels safe,” says Tatev. “We feel only that there is huge danger in our everyday life.”

The rebuild continues

According to local media, most of the 90,000 people who fled to mainland Armenia during the war have returned. But with many parts now under Azerbaijani control, returnees without a home to come back to have been allocated housing in and around Stepanakert.

At the Sofia Hotel and Hotel Europe in the centre of town, the government has rented rooms for displaced families to stay in. Apartments in the capital have also been made available at subsidised rents, reshaping neighbourhoods in the process.

See also | Letters from Yerevan: a city in shock as the nation mourns

At the same time, a mass housing construction project is ongoing. In March 2021, the Armenian government announced a $210 million spending program to rebuild the region’s housing and infrastructure.

Plans for 4,000 new homes are already underway, with further construction projects approved every week. Entire towns for displaced people are forming in the Askeran and Martuni districts, such as the as-yet unnamed village being built between Astghashen and Patara. There, the first round of housing is expected to be ready by this summer.

In Stepanakert, 1,000 new apartments have been promised to families in the next two years. On Tumanyan Street, for example, 108 families displaced from Shushi are to be allocated housing by September.

A French language centre in the capital also continues to be built, as a part of an effort to internationalise the region, which has governed itself as the Republic of Artsakh since 1994 but without formal recognition from any UN state.

Armenian Geographic, a tour operator in the area, has begun taking tourists on trips across Nagorno-Karabakh again, though access for foreign travellers is tricky whilst the conflict remains tense.

“Right now, it is safe and easy to operate tours in Artsakh” says one of Armenian Geographic’s tour leaders. “We have taken tours three times since the war and soon we will go again.

“It is a little difficult to enter if you are a foreign tourist, but we think that soon it will be open for everyone and anyone can travel here. There is a lot to see.”

Sunset over the capital Stepanakert / Lika Zakaryan

Sunset over the capital Stepanakert / Lika Zakaryan

Nagorno-Karabakh is a predominantly mountainous region / Armenian Geographic

Nagorno-Karabakh is a predominantly mountainous region / Armenian Geographic

Daily life and a return to normality

In the meantime, back in Stepanakert, people try to return to normality as the rebuilding effort continues.

“People are doing their everyday routine,” says Tatev, who also heads Artsakh’s public radio station. “If you don’t read the news, you would think that there was no war at all. Just people with sad faces.”

See also | Nagorno-Karabakh: the end of Armenian control

Whilst almost everyone is still mourning the loss of loved ones, the city’s central streets are full of people shopping and going for walks. National flags line the streets, and laundry hangs from washing lines across residential roads, just like before the war.

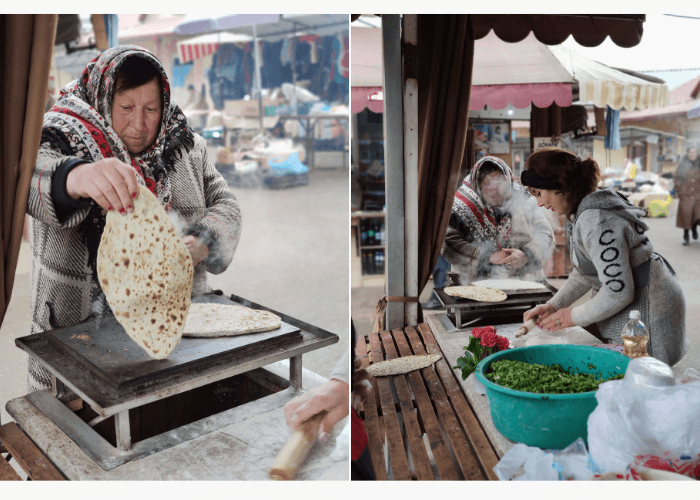

In the centre of Stepanakert, just off Azatamartikneri Avenue, the town’s market is abuzz with shoppers. Traders sell brightly coloured fruits and vegetables stacked up high, as well as meats, preserves and zhingyalov hats (flat bread stuffed with greens) fresh from the grill.

Stallholders make zhengyalov hats at Stepanakert Market / Armenian Geographic

Stallholders make zhengyalov hats at Stepanakert Market / Armenian Geographic Traditional preserves stacked up high at one stall in Stepanakert Market / Armenian Geographic

Traditional preserves stacked up high at one stall in Stepanakert Market / Armenian Geographic

The place is packed with city locals and displaced people alike, though stallholders say people are buying less since many now live on government subsidies.

Children have returned to schools and regular education, having had to study as refugees in Yerevan or not at all during the war. “There is a problem with children whose schools stay under Azerbaijani control,” says Tatev. “Our ministry decided to add them to other schools [in Stepanakert].

“The subjects and lessons are the same. There is only one difference. Pupils are learning about heroes, graduates of their schools, who died during this war.”

An uncertain political outlook

The ceasefire is supervised by a Russian peacekeeping force, and many here have praised Moscow’s role in helping to prevent further Azerbaijani attacks. However, some say that Russian intervention should have come sooner in the conflict.

Moreover, the lack of international recognition for the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh – from Russia or any other country – remains a sore point for locals. For them, the unrecognised status offers legitimisation to what they see as Azerbaijan’s attempts to ethnically cleanse the region.

See also | The Battle for Shusha: the cauldron of generational pain at the heart of the Nagorno-Karabakh war

Since the war, there have been some limited efforts to provide such recognition. In December 2020, the French parliament passed a resolution urging its government to recognise the breakaway state. Similar motions were adopted by the Catalan parliament as well as various local governments in Europe. On the whole, though, the EU has stayed apolitical in the dispute, unwilling to upset important trade and strategic partnerships with Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Right: Flag of the internationally unrecognised Republic of Artsakh flying in Yerevan / Garik Avagyan; Left: Slogan ‘Recognize Artsakh’ inscribed on unexploded rocket in Nagorno-Karabakh / Armenian Geographic

Right: Flag of the internationally unrecognised Republic of Artsakh flying in Yerevan / Garik Avagyan; Left: Slogan ‘Recognize Artsakh’ inscribed on unexploded rocket in Nagorno-Karabakh / Armenian Geographic

An Azerbaijani tourism advert spotted at a London Underground station on 18 March 2021, claiming the town of Shushi (Shusha) as Azerbaijan’s “Cultural Capital” / Ada Wordsworth

An Azerbaijani tourism advert spotted at a London Underground station on 18 March 2021, claiming the town of Shushi (Shusha) as Azerbaijan’s “Cultural Capital” / Ada Wordsworth

Speaking at the end of last year, Russian President Vladimir Putin said that if “normal everyday relations” could be restored between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in the conflict zone, it might create an environment for finally determining the region’s status.

Nonetheless, with ethnic tensions at an all time high, “normal everyday relations” seem to be a distant prospect.

Many in Stepanakert are also upset with the Armenian government, and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in particular, for having failed to adequately prepare for an Azerbaijani attack.

See also | Tatik and Papik’s Second Life: an interview with the Dilakian Brothers

He has been accused of being a “traitor” for having agreed to what many see as a humiliating ceasefire with Azerbaijan, including the loss of control over large parts of Nagorno-Karabakh.

“The mood towards Pashinyan is the worst,” says Tatev. “You can feel only hate.”

New elections in Armenia are scheduled for this summer, but they are unlikely to change much on the ground in Nagorno-Karabakh. Amidst the political uncertainty, the people of Stepanakert can only continue to try to rebuild their lives and deal with the hand that fate gave them.