In the Pandemic Season, Balconies Become Galleries in Russia5 min read

When Russia began gradually enforcing quarantines in late March, the country’s art community followed suit. Galleries transitioned to online, performance art became virtual, and recreating famous artworks via Instagram went viral.

One project, #HermitagefromHome (#ЭрмитажДома), a collaboration between the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and the hip Petersburg-based Sobaka Magazine, challenges participants to post home reenactments of any artwork from the Hermitage’s collection 3 million-plus pieces. Instagrammers used whatever was at their disposal, including laundry detergent, brooms, dishes and pets.

Another popular platform is the Facebook page Isolation (Изоизоляция | Izoizolyacia), which describes itself as a “Covid Anti-stress Art Flash Mob.” It also asks participants to reenact famous artworks, this time from any museum collection. That said, its exhaustive rules page strongly discourages repeating artworks that have already been posted and specifically bans works that are too obvious, namely: “The Lovers” by René Magritte, “32 Campbell’s Soup Cans” by Andy Warhol, and Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square.” “Be original,” they sternly tell us.

On 21 April, the Street Art Museum (SAM) in Saint Petersburg announced its own home isolation contest: an open call for art-makers to create pieces for their balconies and windows. The contest is open to professional artists and amateurs alike from anywhere in the world.

Artist: Nadya O

Artist: group bez.nac

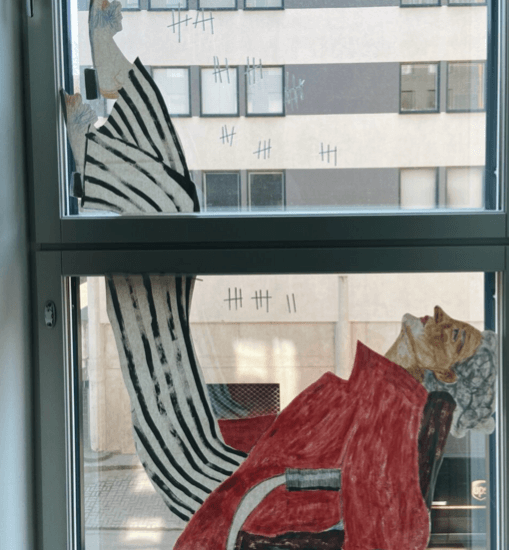

“64th day of emigration, 41st day of quarantine” by Nastya Mazur-Skrobova, a Russian artist who is currently living in Tallinn, Estonia.

Window statues by @mukhanov_vlad

As in other art communities around the world, the quarantine has had different effects on Russian artists, both economically and creatively. Some told me that the quarantine has contributed to their practice – giving them a new topic to focus on and more open-ended time for reflection.

For Ksyusha Pilipetskaya, the artist of the Saint Petersburg-based light installation “Sidi Doma” or “Stay Home,” window-balcony art is a way to offer her neighbors relief from the dullness of having to look at the same view day after day. “I hope to support others by inserting my images into this endless Groundhog Day we’re living through,” she said.

Other artists, like Van Gee of Saint Petersburg, said the pandemic has not changed his practice. “Even in normal times, life in Russia is not exactly simple — you’re always out of your comfort zone.” This situation is obviously more pronounced, he added, but since it’s only been a couple of months and there is no shortage of art supplies, his practice has remained steady.

Artist Van Gee displays his work in Saint Petersburg

Tatyana Pinchuk, the director of the Street Art Museum, worries about opportunities for young Russian artists in a post-pandemic world. So far, Russian regional governments have done little to support cultural spaces (particularly private museums) during the pandemic.

In an interview with Sobaka Magazine published in April, Ms. Pinchuk said that when she asked Saint Petersburg’s Vice Governor Vladimir Knyaginin why cultural institutions were not given support from the government in its coronavirus assistance plans, Mr. Knyaginin said that the government had “forgotten about culture,” but that they would come up with new plans soon.

Even before the pandemic, the market for contemporary art in Russia was limited by lack of funding and political censorship. Now, the environment will be even tougher.

“There is no market for contemporary art in Russia and there won’t be,” Ms. Pinchuk said. “Young artists will leave Russia to search for an audience and like-minded people abroad.”

That said, Ms. Pinchuk thinks the pandemic will increase Russians’ interest in art. Art supply stores, for example, have seen upticks in purchases as more people are drawing and painting as a way to pass time. Ms. Pinchuk predicts that this need for a creative outlet will make people more curious to visit museums and cultural spaces, once they can open again.

Cartoon by artist Tata Tsyrlin in Saint Petersburg. The dog is saying “Woof” and the human, “Got any spades?”

Artworks displayed on Ekaterina Muromtseva‘s balcony in Zagreb, Croatia. Photos courtesy of the artist.

By Anna Timkova, a Russian artist with Uzbek citizenship.

Timkova’s artwork is a giant registration slip, the paperwork that Russian landlords are required to submit when they have foreigners living in their apartments or staying at their hotels. The only word Ms. Timkova has filled out on her gigantic registration form is “Saint Petersburg.” Here is an excerpt from Ms. Timkova’s artist statement: “This is a blank registration form. It’s like paper proof that you have a “home.” These are my reflections on that subject: How can there be a “temporary home?” Or is home the place where you are registered? Or is it the house where you were born? Or is it the place where you have a temporary registration?”

Balcony art by Sasha Ardman. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This article was originally published on Culture P.S. (Post-Soviet)