The Space Adventures of Russian Orthodox Saints10 min read

Russian cosmonaut and practising Orthodox Christian Sergey Ryzhikov may have been born on Earth but currently, he resides among the stars, firmly in God’s territory, on the International Space Station (ISS). Earthly parishioners of St Vladimir’s Orthodox Church in Houston, Texas were treated to a glimpse at the cosmos when Rhzhikov teleconferenced worshippers from the ISS, answering questions about Russia’s scientific discovery of the heavens. This technological link between terrestrial and sky-dwelling Orthodox Christians speaks to a greater connection growing between the earthbound church hierarchy and those Russians exploring the realms above.

Since the shattering of Soviet state atheism, icons and relics have frequently passed between Earth and the cosmos as patterns of religious engagement changed in the new Russian Federation. As an extension of this, the expressed personal religious beliefs of the cosmonauts themselves have become entangled with earthly political agendas.

Noting how Russians in space have created a culture of religious observance on the ISS allows us to recognise patterns of interaction between the crew, the Russian Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos) and the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). In the post-Soviet era, the display of religious icons and relics is an increasingly common societal performance, which has become interwoven with meanings related to Russian identity and patriotism. These rediscovered religious practices on earth take on new significance when transported to outer space.

As the Cold War ended and a tentative, cooperative relationship began between the USA and the new Russian Federation, both states agreed to form the International Space Station. The ISS was initially created from a merger of the USA’s Freedom Station and the Russian Mir-2 designs. Russian cosmonauts living aboard the ISS have resided in the Zvezda space module since Expedition 1 arrived there in November 2000. The Zvezda living quarters comprise two sleeping areas, exercise equipment, a toilet and a galley which are used not only by Russians but all astronauts living on the ISS. Zvezda is therefore a hub for multiple forms of international activity on the ISS.

Orthodox practices in the Zvezda module create a distinct Russian culture in space and reflect changes in church-state relations on earth. It is especially significant that US-controlled modules ban the display of religious imagery. Although, since retiring the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA has relied on Russia’s Soyuz rockets and Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to launch transportation shuttles and as a result has willingly turned a blind eye to Russian religious displays onboard the ISS. The International Space Station Archeological Project notes that religious items have yet to be displayed in the US, European or Japanese modules (aside from those related to Christmas), meaning the practices on Zvezda are a uniquely Russian phenomenon.

Iconography in the cosmos

The importance of the display of icons in Russian public spaces did not disappear during the Soviet Union as images of Soviet leaders were replete in public life. Even in Soviet space stations, Salyut and Mir, images of Lenin and other important Communist figures were displayed on the aft wall of the module. Yet God was absent from the public Russian discovery of the cosmos. As Khrushchev once said: “I sent cosmonauts to space, but they didn’t see God”.

God entered the Russian experience of space by joining other national icons on the aft wall. This is a flat space in Zvezda’s living quarters often used as the backdrop of broadcasts back to earth. This area continues to be used for the display of images and symbols with special importance for the cosmonauts residing there such as on Mir. This personal practice reflects changes in post-Soviet religious engagement where private Russian domestic spaces are more likely to contain religious displays.

The aft wall is prominent in broadcasts to earth by all ISS crew members, not only the Russians. Moreover, there is an additional political significance to the icons chosen by both the cosmonauts and terrestrial organisations such as Roscosmos and the ROC. On the ISS, therefore, personal expressions of Orthodox Christianity coincide and interact with institutional and even state-sponsored ways of conveying faith.

The wall of the Zvezda module. Since the disintegration of the USSR, Orthodox saints have begun replacing old Soviet heroes / NASA

The wall of the Zvezda module. Since the disintegration of the USSR, Orthodox saints have begun replacing old Soviet heroes / NASA

NASA posts publicly accessible photos of Zvezda’s interiors on Flickr and a close examination of 48 photos taken between 2000 and 2014, revealed variations in the icons adorning the aft wall mirrored developments in Russian religious and political life on earth. It can be concluded that alterations in the icons on display reflect the changing religious practices of Russians in the post-Soviet era as well as events occurring in Russian foreign and domestic politics.

Trends can be noted in how the display of icons is used to benefit the changing policies of the ROC and the Russian Federation. Through its closer relationship with the cosmos, the ROC connects itself to national institutions constituting part of “Greater Russia”, such as the space programme. In terms of the Russian Federation, changes in the conspicuousness of icons can be observed at times when the regime requires the consolidation of Russian patriotism at home.

Co-operation earthside

Prior to Zvezda, the ROC began collaborating with Roscosmos in ways that reversed the atheist rhetoric typically used by the state to describe Russian adventures in the cosmos. The patriarchate of Alexiy II (1990-2008), which began as the Soviet Union was collapsing, represents a key period in this varying relationship. At this time, the Orthodox Church resumed its central position in Russian society accompanied by a revival in Russian religious life. The institutional efforts of the ROC to establish a presence in space evoke a sense of missionary zeal.

The frequent transportation of icons and relics into space began under Alexiy II. In July 1995, the Patriarch blessed two print icons of Saint Anastasia (one Orthodox and one Roman Catholic), which were then sent on a “peace mission” to the Mir Station. Saint Anastasia was chosen as a symbol of peace as she is a saint common in both Eastern and Western Christianity as well as a protector against international warfare. Hence the project’s name: “Project Anastasia- The Hope of Peace”.

Seven months later, the icons returned to earth and embarked on a pilgrimage across Europe to all places associated with Saint Anastasia. The impact of this move by the Church hierarchy was significant to the Russian cosmonauts living on Mir. It empowered them to adorn their own personal space with icons. Consequently, photos between 1996 and 1998 demonstrate that icons were informally stuck to the walls of the Russian quarters.

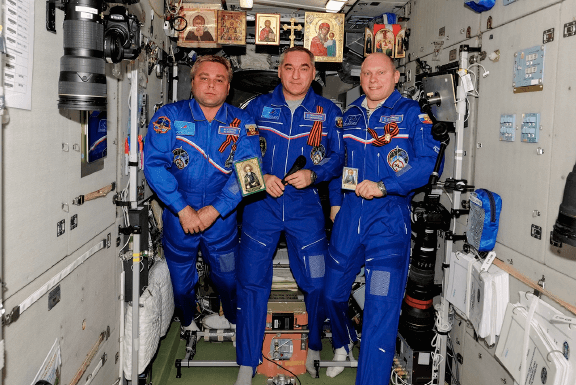

Cosmonauts in Zvezda, 2014, with icons of Saint Sergius of Radonezh / NASA

Cosmonauts in Zvezda, 2014, with icons of Saint Sergius of Radonezh / NASA

The missionary enthusiasm of the Church also found a pathway to the cosmos through the thoughtful cultivation of personal relationships with key personnel in Russia’s space programme. For example, Head of Roscosmos Anatoliy Perminov enjoys a close, personal relationship with the ROC, established during the patriarchate of Alexiy II. Perminov met repeatedly with Patriarch Alexiy and continually expressed a desire for mutual cooperation with the Church. Indeed in 2008, Perminov gifted him with a GLONASS System Satellite navigator as a Christmas gift. The evidence of deeply personal relationships between ROC and Roscosmos is also noticeable in the friendships between Russian cosmonauts and Father Yov Talats, rector of the Cathedral of the Transfiguration. This church is located in Star City where the Russian cosmonaut training facilities are located.

Father Yov is present when Russian cosmonaut teams are sent off from Baikonur, and meets them upon their return. In his public engagements, the clergyman often recounts his childhood dream of becoming a cosmonaut and, even after becoming a priest, took part in aspects of cosmonaut training. Yov works from the Trinity Laura of St. Sergius, an extremely significant centre for the ROC, where departing Russian ISS crew members are blessed before they leave for Baikonur. Recently, Father Yov has acted as a religious mentor for members of the Russian ISS crew and has arranged for holy relics to be sent into space in the care of his flock.

Heavenly journeys, earthly implications

The ROC under Alexiy II forged close ties with Roscosmos and oversaw the initial transportation of icons and relics into space. After “Project Anastasia”, a cult began to form around these icons that had travelled to space upon their return to earth. These icons took on a new power for Orthodox believers due to their exposure to space. Head of Roscosmos Perminov himself announced, “already the icons of Kazan Mother of God and the Archangel Michael, after many times orbiting our planet … will come to reflect the combination of traditional spiritual symbols and contemporary achievements in the field of space exploration”.

An example of this is the icon from the Valaam monastery, which orbited the earth over 1000 times in the company of Russian cosmonaut and ISS crew-member Sergey Krikalev in 2005. On its return to earth in 2006, Valaam monks and the cosmonauts who accompanied it home claimed that the icon was capable of miracles and had ensured a difficult landing was carried out safely.

Icon of Christ Pantocrator and gold cross floating in front of the front hatch of Zvezda / NASA

In this way, the transportation of religious icons and relics to the ISS is seen as a new form of the Orthodox krestnyy khod [Crucession or Cross Procession] The Crucession is a religious event that takes place on important dates in the liturgical calendar and involves large processions for the veneration and public conveying of icons or relics. As the abbot of the Valaam monastery himself stated, “the tradition of the religious procession is ancient,” yet also “these days, this tradition takes new forms and we encounter an icon that has completed an even more unusual religious procession”. Like the cosmonauts themselves, the icons take on a certain significance having endured the tribulations of space.

ROC Church officials deliberately referred to the transportation of relics of St. Serafim of Sarov to the ISS in 2016 as a krestnyy khod. The box containing the relics was strapped to the chest of the aforementioned Sergey Ryzhikov, parishioner of St Vladimir Orthodox Church and at that time the commander of the Soyuz rocket travelling to the ISS. Upon returning to Earth, the relics were given a place of honour at Father Yov’s church, the Cathedral of the Transfiguration. Crucessions have historically been seen as displays of a national communal faith and therefore new manifestations of the practice have very real implications for creating a sense of national patriotism.

The krestnyy khod has appeared in contemporary Russian legend during times of national insecurity. In 2013, gossip circulated that Vladimir Putin had carried an icon in a helicopter over Volgograd after the suicide bombings in the city. This reflects similar rumours that spread as the Nazis were about to capture Moscow during the Second World War that Josef Stalin himself had flown over the city accompanied by an icon.

To infinity… and beyond?

It follows that displays of religiosity on the ISS differed from the peace-building sentiment behind “Project Anastasia”. Rather, icon displays were more connected with political life and religious revival on earth. Icons and relics from Russian Orthodox saints continue to travel to the celestial domain but their journeys speak more to terrestrial dynamics of power as Russia and its national church extend their influence into the cosmos.

Parishioners watching Sergey Ryzhikov from their pews in Houston must have felt him very far away as he floated among the stars, an awe-inspiring personification of Russia’s expansion into all realms of human activity. Yet the relationship between Russian cosmonauts and the earthly politics of religious engagement remains much closer than the yawning void of space between them would make it seem.

The is article draws on research made by Wendy Salmond, Justin Walsh, and Alice Gorman.