Pop Feminism: how Central Asian artists are using social media to create change7 min read

For centuries Central Asian society has restricted women’s rights according to religious canon or cultural patriarchal prejudice. Growing up in Kazakhstan as a woman, it is common to hear that our primary duties are housekeeping and childbirth. Any other initiative outside of marriage is considered uyat [shameful].

Today most Central Asian countries have adopted more Western ideas of freedom and equality through exposure to foreign media and the Internet. Still, girls are introduced to customs around prospective marriage at a very young age.

In school, girls are taught how to cook and sew, while boys learn how to make repairs and are introduced to military studies. Later in life, women often face gender discrimination in the workplace or domestic violence upon marriage.

In recent years these old-fashioned stereotypes have been actively challenged by young local artists, who are bringing issues related to gender discrimination to the forefront. This new generation is trying to spread awareness, redirect culture and create a more peaceful, equal, and respectful society.

No justice

Domestic violence and sexual harassment are quite common in the region due to economic struggles and cultural belief that women are weak and should be submissive and obedient. The number of cases increased following quarantine restrictions: in the first half of 2020, Kazakhstan’s police received more than 46 thousand calls of domestic violence, while Kyrgyzstan’s police saw a 65 percent increase compared to 2019. 9,025 cases of abuse were reported, but only 940 made it to court.

In Kazakhstan, a local NGO called NeMolchi KZ has been sharing stories of women who faced harassment and provided them with legal counselling since 2016. Last year, one such story caused a public outcry. While working at a bar on March 14, Ainagul Bekenova, 28, was attacked with a knife by her ex-husband after she had refused to get back together with him.

Bekenova survived but had multiple deep cuts across her face. A case was launched only after the attack was made public. As a result, her ex-husband was sentenced to four years in prison in October 2020. The NGO was able to connect her with free psychological support and a plastic surgeon.

Although legally the police are supposed to work on these cases following victims’ reports, they are commonly disregarded as they are considered to be family matters that do not belong in a courtroom. In Kazakhstan, “light” cases of domestic violence were de-criminalized in 2017. However, discussions about a potential re-criminalization are being planned by the current administration.

A violent tradition

Another form of violence against women that is still perpetuated in both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan is an old, and nowadays illegal tradition called alyp qashu in Kazakh, or ala kachuu in Kyrgyz. This is the practice of abducting a girl with or without consent and forcing her to marry her kidnapper, who, in some cases, might have also raped her.

Common motivations for bride kidnappings include trying to avoid the expense of hosting a wedding, a prior arrangement with relatives, presumed rejection from a prospective bride, submissiveness from the woman’s side – or to cover up pre-marital sex and subsequent pregnancy outside of marriage.

In many cases, the girl does not know the abductor and sometimes there is a big age difference. Due to the belief that they will be cursed to live unhappily or be shamed and judged by society if they refuse, most women end up staying with the abductor. A few run away and try to be accepted back into their families and communities. Some end up committing suicide.

Authorities do not keep statistics on the matter and most cases remain unreported. These forced marriages are widespread in rural areas of Kyrgyzstan and southern Kazakhstan. A Human Rights Watch report from 2006 showed that roughly 40 percent of women in Kyrgyzstan had married through non-consensual bride kidnapping. In 2018, Radio Azattyk reported that 20 percent of marriages happen through bride kidnapping in the same country.

In 2019, the Kyrgyz Criminal Code was amended to include a prison sentence of up to 10 years and a fine of 220 000 Som (2155 Euro) for bride kidnapping. In the last five years, out of 895 filed statements, 727 were never prosecuted.

The Kazakh Criminal Code does not separate bride kidnapping from general kidnapping; abductors might face up to 7, 12, or 15 years depending on the circumstances. If the kidnapper frees the victim, he will not face any criminal charges.

The voices of a new generation

Today, traditions, where women are downgraded and made to serve as an accessory value in men’s lives, do not satisfy the young minds that grew up seeing the violence that was tolerated by their parents and grandparents. They have strong opinions on human rights and are eager to defend them from abuse and neglect. They are the product of independent Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Zere Asylbek is a 22-year-old Kyrgyz singer-songwriter, who releases songs on various political issues on her YouTube channel. Lyrics from her first single from 2018 Kyz addressed gender discrimination:

I wish the time passed; I wish [a new] time came

When they wouldn’t preach to me how I should spend my life

She actively participates and helps to coordinate peaceful marches in Kyrgyzstan, including in support of women’s equal rights. Her newly released song Apam Aitkan touches upon inequality, victim-blaming, and sexual harassment against women, including bride kidnappings:

Mom used to say “Never stay alone, my daughter”

Mom used to say “Do not be outside in the evening, my daughter”

Mom used to say “There are different kinds of people [out there], be careful, you are a girl, be careful”

Another singer-songwriter from Kazakhstan, Danelya Sadykova, 21, used Instagram to share her story of sexual harassment. In February of last year, she spoke up about an incident at a local music platform event, where two Kazakh rappers, KC and Bonah, inappropriately touched her.

Daneyla Sadykova used Instagram to talk about her experiences of sexual harassment / Daneyela Sadykova

At first, the rappers accused her of using it as a PR campaign for her album, but following a backlash, apologized for their wrongdoings. Many women were inspired by her posts and began sharing their stories – including famous artists like Nazima.

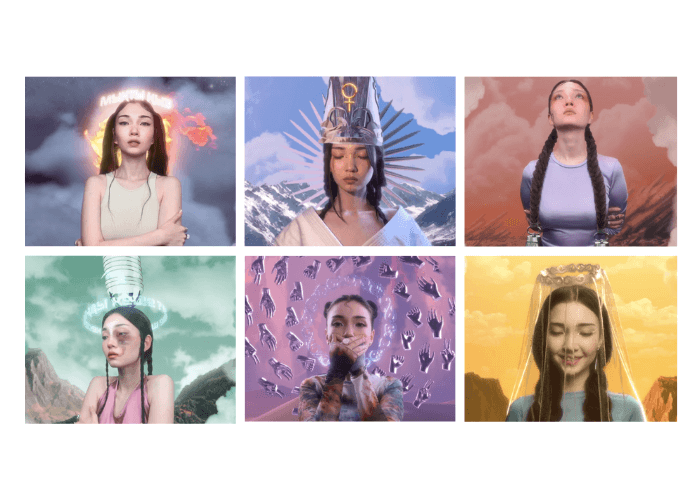

In 2020 Aya Shalkar, 25, an artist also from Kazakhstan, created the alternative reality video campaign Aiel to discuss domestic violence, bride kidnapping, sexual harassment, victim-blaming, and discrimination against women in the workplace, in politics, and in Kazakh society in general. Her project includes six short videos created during the quarantine.

Stills from Aya Shalkar’s campaign Aiel (2020) about women’s rights in Kazakhstan

The campaign demonstrates the struggles women experience in an eye-catching manner. One of the videos shows how 40 hands carve out a girl’s destiny while her mouth is covered and voice silenced. It is inspired by a Kazakh proverb about expectations placed on a girl by forty households [referring to society].

Aya uncovers oppressive traditions which might not be obvious and point out the roots of gender inequality to her Instagram audience of more than 720 000 followers. She is one of the most famous and influential media personalities in the country. Her goal is to create a safe space to discuss gender inequality and vulnerability and empower women to be strong and independent.

Similar issues were explored by Kazakh filmmaker Kana Beisekeyev, 29. In 2021 he released a documentary called The Wife on domestic abuse. It features the personal experiences of a number of women and men who read their stories to the camera. The documentary also highlights that UN statistics show that 400 women die annually due to domestic violence in Kazakhstan. One of the stories told that domestic abuse is not only wife or partner-oriented, but that children can be victims too.

Hope for the future

These emerging voices from a generation of independent Central Asian republics spread awareness on gender discrimination primarily through social media. All of the artists mentioned have a big number of followers who look up to them and participate in protests and marches that usually take place around International Women’s Day. The work of NGOs like NeMolchi KZ also contributes to the long way Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have to go through before gender discrimination is eradicated. They destroy traditional boundaries and affect young people’s mindset by sharing stories that the older generation would brush under the kitchen table.

Awareness is key to societal and political change. If words can spread to all remote areas, ideas about unquestioned traditions and customs can also change. By bringing attention to traditional root causes and violent consequences, Kazakh and Kyrgyz artists are incentivizing legal changes in relation to gender inequality, domestic violence, and bride kidnappings. They use their platforms to encourage women to speak up, society to stop victim-blaming, and lawmakers and the general public to act on abuse that might be just next door.